I live in exile now, as many of my people do. Once I lived in my homeland, Tibet in the midst of the Himalaya Mountains. I was born in a village, called Kalagunpa, in Kham, Eastern Tibet. My people were nomads, called Khampas, and my village was grassy with fields, little hills, and many rivers. My house was square-shaped and made of stone and mud. The roof was made of sticks taken from bushes, and on top of the roof was room to store grass for the cattle to eat during winter. In the winter we remained in our village, but during the summertime we left our house and lived in a tent made of yak hair (in Tibetan it’s called a bu) and with our cattle we moved around from place to place. Sometimes as many as fifteen families would travel together and follow their cattle. I lived with my mother and brother, and never knew of my father.

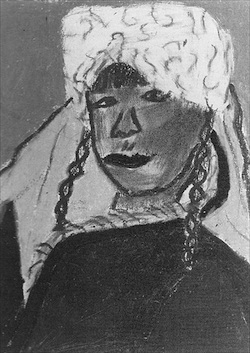

My mother was very beautiful. I called her Amala, which means “mother” in Tibetan. She had long black hair that was woven in many little braids. She wore many ornaments made of jewels. Above her forehead was a big yellow stone with a small red one behind it, both tied into her braids. She had big round earrings made of silver and turquoise. Many small bells dangled from her back and made her movements sound like music. All the women in my village had a yellow-and-red hair ornament and many bells, but my mother was known for her beauty.

She worked very hard. We had cattle, and early every morning, when it was still dark, she woke to milk the cows. Then she would cook breakfast for my brother and me, which was usually roasted barley porridge called tsampa. Afterward, she would make cheese and butter from the milk.

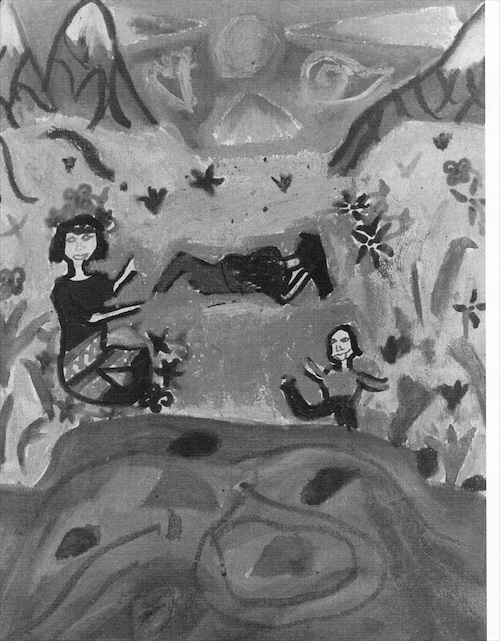

Like most Tibetans, my mother believed in Buddha. We had an altar with a picture of Karmapa, our spiritual leader, and many butter lamps and burning incense. Every night my mother would do prostrations in front of the altar and say prayers. Sometimes I would do prostrations with her, but I was always joking when I did. Amala would say that all she ever wanted from life was for my brother Karma Tenzin, to be a monk and for me, her little girl, to be by her side. But I wasn’t by her side; I was always outside playing. In the summers, when we moved around, I spent all my time by the river playing with friends. We would jump from rock to rock across the river trying not to fall in. There were many sheep, yaks, goats, and horses where I lived. And we collected black and white rocks from the riverside and pretended they were different animals. My village also had lots of flowers, and my friends and I would sit in the grass and string the flowers into garlands for our heads.

Tenzin was a monk. He was thirteen years older than I, so in some ways he was kind of like my father. Tenzin became a monk when he was fifteen. I was about two at the time.

There was one very special lama in my village named Karma Norbu Rinpoche. My people called him the second Milarepa. He wore only white cotton clothes and was bare-armed all throughout the frozen winter. Rinpoche lived in a holy cave above my village and meditated a lot. He was very respected. When the Chinese invaded my village, he was one of the lamas who was made to lie down and have ladies jump over him. This is a horrible thing for Tibetans to do, because lamas are spiritual teachers and to jump over them is disrespectful. The Chinese put him in prison. He was a very spiritual man, and even though the Chinese would punish and punish him, he would love them in return. They tried to starve him by not giving him any food for a long time. But he was magical, and when the soldiers would come to check on him, instead of being weak and thin, he was fatter and fatter each time. Finally after eleven years, the Chinese let him go free because whatever they did to him, the lama was happy and loved them.

When I was six and a half, my mother became very ill. At first she was weak and tired. One morning, while tending the cattle, she didn’t come back to the house with the milk. Tenzin went to see what had happened.

In Tibet, when someone dies, the body rests in the house for three days so people can view it. I remember now that during this period I was playing outside with friends and a girl said, “Oh, Dolma, your mother is dead,” and I said, “No she’s not, she’s inside my house.” After three days, the body is taken to a particular spot on the mountain, cut up into pieces, and fed to the vultures. This is called a sky burial.

After my amala’s death, my uncle said that for the time being I was to live with his family. One day, Tenzin came by and said he was going to make a pilgrimage to Lhasa. Tenzin would be doing prostrations the entire way instead of walking because it was more religious, and he would gain more spiritual merit for Amala. All of these offerings and prostrations would help my mother have a better reincarnation. It was going to be a very important religious journey.

Tenzin went to visit Karma Norbu Rinpoche in his holy cave. He asked him whether it would be good to go on pilgrimage, and Karma Norbu Rinpoche replied that it would be very good, especially since both of Tenzin’s parents had died. But, he said, instead of walking it would be better to do prostrations. It was much more of a sacrifice. Rinpoche told Tenzin, “Your sister, Dolma, must go with you to Lhasa.” Tenzin said, “I can’t take Dolma; she is very young. It would be too difficult. I will be doing prostrations—how will I care for her? The path to Lhasa is long and dangerous.” But Rinpoche only said, “She must go. The two of you must go together. You may die along the way, but you will die together. If not, you will live together.” So Tenzin decided he would take me along.

He started preparing for the pilgrimage. He asked some people to make a tent of white cotton. He asked a friend’s mother to prepare tsampa from the grain he had bought, and he asked a friend of my mother’s what he would need while he did prostrations. The friend told him that he would need to make sa-gas, which people wear on their hands, like strong gloves, for protection, and he would also need leather clothes to protect his body. After that was finished, Tenzin had all the food, clothes, tent, and a horse, and was prepared to leave for Lhasa. He told my uncle, “Now Dolma and I will make our pilgrimage.” Everyone in our village was talking about the two orphans who were going on pilgrimage alone. My relatives were very worried, and they held a meeting.

My auntie went to Karma Norbu Rinpoche in his holy cave and asked him if it would be good for her to join us on pilgrimage. Karma Norbu Rinpoche knew of three monks and a nun who were planning to prostrate to Lhasa too, and he arranged for all of us to go together. So our group was Tenzin, myself, my auntie, three monks, a nun, two men to tend horses, and three horses. Chu-wong, an old man with gray short hair, was one of the monks. Nomay was the very tall and strong monk who carried me on his shoulders whenever we crossed a river. So-da was the monk who was always getting sick, and Sa-tan was a pretty young nun. I didn’t really notice she was a woman because her head was shaved. She wore the same clothes as the other monks. Tenzin was the youngest monk in the group.

Together we left our village. The four monks and nun, including Tenzin, started doing their prostrations, all in a line. They looked very beautiful touching their hands together above their heads, to their heart, and then bowing with their head and bodies on the earth. My auntie was holding my hand; she seemed sad to leave her children and family behind. I could tell she had been crying.

That night, we camped next to the river and had tsampa and butter tea for dinner. At 5:00 A.M., we again had tsampaand butter tea, loaded our horses, and started off. I began to understand that the thing to do was to walk for a while, and then stop to wait for the people doing prostrations. It seemed difficult to prostrate all day long. Tenzin’s body was sore. He had dust in his eyes, and his head hurt from rubbing against the ground. Every morning we awoke before dawn to have breakfast. At dawn, we would leave, the monks and nun all prostrating, Auntie and I walking and waiting, walking some more and waiting.

Around noon, we would find a place to camp. We set up our cotton tent and found grass for the horses to eat. Tenzin and Auntie would go out and fetch water to cook with. Often they would find a nearby village and go from house to house asking for food, or cooking utensils, or yak dung to make the fire. This was how we ate mostly. We broughttsampa along with us, but only for when we couldn’t find any people. Even if a family was very poor, they would give us some of what they had. People never refused. It was considered good luck for a person to help a pilgrim on a holy journey. Sometimes Tenzin would buy meat and butter in the villages, and we would eat that.

When we had been walking for over a week, the land began to change. The river had gotten much wider and the rocks were different colors than the ones found in my village. One day while everyone was setting up the camp, I found a branch of smooth wood that I decided I would use for a walking stick. It was the perfect size for me, and I was very excited.

The first place we visited was a small monastery. We went into the temple and all made prostrations to the images of Buddha. We offered butter to be used in making the butter lamps that lit the temple. Tenzin prayed and asked Buddha to help all living things, to help them from suffering, and to bring all living beings peace and happiness.

The next day I saw the most curious animal. I was walking along and saw these very tall animals, like giants. They each had one leg that was brown, and they all stood together in a line. They also had many arms reaching in all different directions. And their hair was many little green circles. I asked, “Brother, brother, what animal is this? Are they sleeping?” “These are no animals, Dolma,” he said, “They cannot walk. These are trees, and trees are plants.” Soon we were in a forest, and it seemed strange that I had never seen a tree before because there were so many. The forest was shady and dark. I wondered why my village did not have these tall trees with many arms. I wanted to explore this forest. I liked the little areas where the sun crept through the trees, and in the middle of all the shade was a circle of bright light. I could notice that it was getting darker. Then all of the sudden these hairy animals saw me and stood up like men. They made noises that were like screams. I got scared and ran back to the tent, “Auntie! Auntie! What kind of animal screams and walks like you and me, but it’s hairy and fat with a tail?” “Oh that,” she said, “It’s your father.” “My father?” I asked. “No,” she said, “it’s your father’s brother.” She was joking because my auntie did not like my father. “The animal you saw was a monkey.” “Oh! Can I go catch it?” “No, Dolma, because monkeys like to grab little girls.” So I didn’t go looking for the monkeys, but that night as we slept they opened our tent, ripped it, and stole some of our food.

One day we came to a bridge that we had to cross. The ravine below was very far down and filled with very deep water. The bridge was made of old wood and was narrow and very long. It looked like it would break if someone even stepped on it. I thought I might die if I went on it. “Dolma, you must cross this bridge. It is the only way to get to the other side,” Tenzin told me. “I will return to our village,” I said. “Follow behind me,” Tenzin said. But I just sat there in front of the bridge and did not move. Everyone else had crossed and was waiting for me; Tenzin came back to get me. “Please, please, cross the bridge with me, Dolma.” I would not. Then Tenzin said, “All right, but you will have to walk back to the village all alone. It will take you months, and jackals will try to eat you.”

I took slow steps and said, “Om mani padme hum” with each step the whole way. This means “Hail to the jewel in the lotus” and is talking about the Buddha. It is a mantra that all Tibetans say. When I finally got across, everybody had been waiting for a long time. They said to me, “Dolma, you are not brave.” But I felt brave for crossing that bridge, even if it did take a long time.

One day Auntie was teasing me a lot, and I said to her, “Auntie, you are always teasing me, but you never tease Tenzin.” And she said, “Tenzin does prostrations all day long, each step. He does not deserve to be teased.” I told her, “I want to do prostrations to Lhasa. I can do it.” “Okay, okay. If you do that, I will wash all of your clothes for you, and I’ll feed you, and I won’t tease you any more,” she said to me. So I went to my brother and said “Tenzin, tomorrow I will do prostrations with you.” The next morning, Tenzin gave me his sa-gas to wear on my hands so they wouldn’t become sore. On this particular day, we were going up a big hill. So I had to make my prostrations going upward. It was so difficult. The sa-gas would slide off my hands and land in front of me because they were too big. My stomach would crash to the ground and hurt. “Slow down, Dolma,” Tenzin told me, “If you prostrate slowly, you won’t hurt your stomach.” But I wanted to keep up with Tenzin and the others, and they prostrated very fast. I had told myself that for the entire day I would make prostrations, and I did.

When we reached the area to set up camp, I was very tired. I had dust in my eyes and my whole body hurt. I ate and went straight to bed. The next day my body still hurt, and I walked very slowly beside my auntie. I decided not to do any more prostrations. Everyone teased me and asked if I wanted to do prostrations the following day. I had a new respect for my brother and the others who prostrated each step of the way, each day.

It had been snowing for a couple of weeks now and was very cold. It was much harder for people to do their prostrations, and our group was moving much slower. Early one morning we came across a huge river. There was no bridge, but we needed to get to the other side. The river was flowing very quickly, and the water was ice cold. Tenzin and the four others decided we must cross by walking. We loaded the horses, and then each adult got in the river. Linking hand to hand, they made a bridge of people. The whole time, I sat on the shoulders of Nomay, so I stayed dry. When they were all in a line, they took a rope and pulled the horses through the line, across the river. I looked over at Tenzin. His teeth were moving and making noises, his body was shaking and the water was up to his chest. It kept snowing harder. Finally when everybody had crossed, we were safe. Everyone was wet and shaking. They said they couldn’t feel their hands and feet.

Soon after that, we had to cross a mountain called Ja-la. Again it was snowing very hard. It was difficult to see anything, but they did not stop prostrating. It was so cold I could not feel my hands or the tip of my nose. The paths were much harder to find because of the snow, and it seemed like we would never make it. I cried a lot and said I wanted to go home. They told me to keep moving to stay warm. After we crossed Ja-la and made our tent, we had trouble making a fire. During the journey we had to take everything off the horses because it was too heavy for them. All our things were now wet. After a lot of looking, we found some dry yak dung and lit a fire. Auntie made many cups of butter tea to warm us. Everyone was still so terribly cold and numb that they could not feel their hands. The horses were tired and didn’t look too well either. We couldn’t find any grass for them that night. I gave them a little tsampa.

Some weeks passed, and we didn’t come across any villages. Our own supply of food was running very low. It was becoming colder, and everyone was getting sick. We came to an open field and didn’t know which direction to go to Lhasa. That night the monk named So-da got very sick, and we couldn’t leave the next morning. It was snowing, and there was no place for the horses to graze. They also became very thin. During the days, Tenzin and the others would walk around trying to find a village or some people. So-da was still very sick and stayed in the tent all the time. I didn’t really leave the tent much either because my stomach was bad, and there was so much snow. We would melt the snow and drink the water. I could tell that the grown-ups were getting scared because we were running out of food.

Finally Tenzin found some people, and he returned with grass for the horses and enough food for all of us. They even gave him some meat, and we felt saved. Two days later So-da had recovered and we were ready to go off again.

One morning, far across the distance, I could see a snowy mountain. Later I learned that it was a mountain made of piled prayer rocks. It was very holy. Each rock said “Om mani padme hum” in a different color. This holy mountain was called Chija-ma. It is very famous in Tibet.

After twelve long months of many rivers and mountains to cross, sunshine and snow, many prayers and prostrations, many difficulties and much wonder, finally we reached the heaven place, the Holy City, Lhasa.

My eyes felt as if they were popping out of my head. For, though I saw many new things along the way, it seemed as if there were just as many new things all within Lhasa. The styles of clothing, ornaments, and even the style of speaking were all different from mine. I saw Indian and Nepali people for the first time. They were very dark, and their eyes very deep. There were shops everywhere, and a person could find whatever he or she wanted to buy. There were big, famous temples and many, many monasteries. We visited the famous monasteries and made offerings and prayers and prostrations.

While we were in Lhasa, I made some friends who were older boys from Lhasa. They knew the town well and would show me around. We spent most of our time together at Bhar-kor, the main center of town which surrounds the Jokhang. The Jokhang is a very famous temple with a statue inside that Weng Chen, a Chinese Princess, brought to Tibet many years before. The kora, or holy walk around the Jokhang is lined with stands and crowded with people buying and selling, or walking along it turning their prayer beads or prayer wheels. Right in front of the Jokhang is an area where people do prostrations. There are always people there.

Sometimes, in front of the Jokhang, the Chinese would announce that the next day they were going to kill criminals. They announced where it would be and invited the public. Tenzin told me never to go. He said he would beat me if I ever went. But my chu-chu-las (I called my new friends chu-chu-la, which means “older brother”) wanted to go, and I was interested. I never knew what the criminals had done, but they were always Tibetan. The Chinese would blindfold the criminals, put cotton in their mouth, and then shoot them in the back. It made me a little sad, but I tried not to think about it. One time there was a Tibetan who refused to use a blindfold or cotton. As they shot him he screamed “Karmapa,” the name of our spiritual leader. I will always remember that, and I went home and told Tenzin about it. “Dolma!” he screamed, “I told you never to go there. It is wrong and dangerous. They may kill you.” After that, I never went back again.

After one month in Lhasa, Tenzin and I left again on pilgrimage, this time for Nepal. Tenzin would not be doing prostrations because he had only promised to do them until Lhasa, and it would be too difficult with the two of us alone. My auntie was crying. “Tenzin, it’s too difficult to look after Dolma. Let us go back to the village.” I wanted to return with her and was crying too. We exchanged khatas, or holy scarves, putting them around the necks of Auntie and the monks and nun who had become our good friends. I did not know what the future would bring. I hugged and kissed Auntie one last time. I clung to her for a while, breathed in and smelled her. Then I said good-bye, and Tenzin and I left for our pilgrimage to Nepal.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.