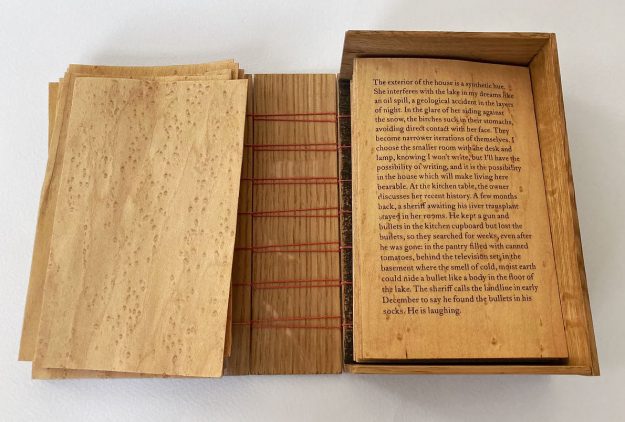

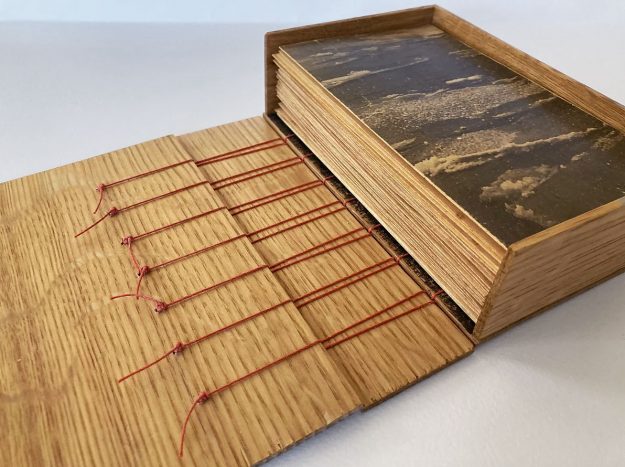

Housed inside a maple box and bound together by a thin red string lies poet Kōan Brink’s newest poetry collection, What Sleeps under Lacquer. Describing the unconventional art object, Brink (who uses the pronouns they/them) says, “The idea for the ‘book’ is that the poems are printed onto wood cards and housed in a box, like tarot or incense sticks. The materials and design are connected to Minnesota, where I grew up—flame maple, photos I took of Lake Superior, ice, etc. printed on wood. I imagine the poems ‘arrive’ in a kind of order, but can be shuffled like a deck over time, or even lost.” The collection will be published this fall by the Austin-based publisher NECK Press.

Brink is also the author of the poetry chapbook The End of Lake Superior, published by above/ground in 2021. They received their MFA in Poetry from Columbia University, and they studied Buddhist texts and social ethics at Union Theological Seminary. Brink is also a lay ordained Soto Zen student practicing with teachers at Brooklyn Zen Center, where they lead a monthly Queer Dharma group.

Tricycle spoke to Brink about their creative process, establishing a sense of place, and the fruitful relationship between poetry and Zen practice.

Your name is Kōan. Can you share the story behind that? I’m assuming that it’s a name that you received from a teacher. I went through a lay ordination process with Brooklyn Zen Center in 2019, so it’s a lay ordination name that was given to me by my teacher. I chose to start using it for a number of reasons. One was around identifying as queer and having such a fluid gender identity in my twenties. It felt really good to have a name given to me by someone who knew me on a much different level and capacity than my parents did. I felt very seen by my given name, and I’m not mad at my parents for having named me Anne. But I don’t particularly identify with femininity in my body and personality. I use non-binary pronouns, and I prefer gender-neutral language. My lay ordination name actually felt better in my body.

When you receive ordination and a new name in Soto Zen, you take vows and precepts. Having my name said out loud by me and having other people use it just reminds me of my vows on a daily basis. It brings me back to having gone through the ceremony and the commitments I made as a Zen student, not just to Brooklyn Zen Center, but to a deeper Zen lineage in Japan, and it helps me honor those ancestors there.

In using my name, there’s a deep reverence for ancestors and a desire to fully connect to the roots of the lineage and continue to learn and be part of that. I don’t take the name lightly at all, given that I’m a white person living in the US and practicing a lineage that did not originate here but has moved here and flourished. It feels important for me to consider the entire context of the name and be honest about why I individually choose to use it, and I continue to reexamine that on a daily basis.

People usually think the name refers to the Zen koan, but it actually doesn’t. It’s spelled the same way, but the characters actually mean “luminous hermitage.” There’s one character that means “light” and then one that means “monastery on a hill.” So it actually just means “light hermit,” basically.

It seems like a lot of your writing is informed by place. Has your recent move from Brooklyn to Austin influenced your writing and meditation practices? I feel like my writing process and the forms that the poems take have been very contingent on the spaces that I’ve lived in. Before I moved out of New York, especially when quarantine started, I was writing a lot of prose poems. This felt connected to being in small spaces all the time and not being able to go outside. I literally felt boxed in; my language felt condensed into all of these small rooms and couldn’t move outside of it. Then I moved to New Mexico very briefly before I moved here to Austin. It was the opposite of being in Brooklyn. There was so much light and so much space, to the point where it was almost a little scary to me, because I’ve been used to working in this really condensed mode in a stressful city. Then I noticed all of the sentences I was writing suddenly became longer, and my language became more spacious.

I feel very affected by light in different places, and I feel very affected by the pace at which my body is moving. That’s something I didn’t realize until I moved.

My partner lived here in Austin before I did, and he had set up the garage into a studio space to have a small press. There’s a risograph and woodshop stuff down there, which is incredible. I never had that in Brooklyn—you’re living in these tiny bedrooms. In Austin, I’m in a large one-bedroom with a garage and a backyard, but I feel like I live in a mansion. When I moved here, I had a number of projects I was working on—namely this journal Rainbow Agate that I created with my friend Chris–and I needed a physical space to finish them.

I’ve been in a mode of finishing projects right now in a way that I didn’t feel like I was able to do in New York because of money constraints, space constraints, and equipment constraints. Living here, I’m in a period in my life that I’ve never been in before.

Can you tell me more about what your creative process is like? I have been in a process-oriented place for the past ten years or so. Especially during and after my MFA, my only materials were my laptop or a pen or a notebook, and I was very transient. I’d kind of just walk around. It was a lot of note-taking and working on poems, but in this kind of ethereal making-space in which there wasn’t ever a completion stage or a finished form. Now, over the past couple months, I’ve been thinking about the book as an object, like: What font would I prefer? How does a poem look with certain margins on the page? What kind of ink do I want to use? How would I want to bind something? What kind of thread would look good with this? I’ve been thinking about poetry in a much more embodied, physical way than I had ever thought about before.

Astrology also informs my entire line of thinking. I have a lot of air placements, and I feel in writing that I’m constantly in this dream-memory, half-asleep state all the time. But I have an earth moon, so when I was binding this book I thought: I’m a physical body, I’m going to make things, I’m going to channel whatever grief and joy people had into this physical form to share, so other people can appreciate it.

It’s been interesting being in this physical construction phase. I have a story about myself that I’m not very good at doing physical things, that I’m an intellectual person who’s shitty at binding a book. I couldn’t even mail some copies of Rainbow Agate because the paper was cut so wonky. The process was all about letting go of making a perfect object.

Can you tell me more about the specifics of your practice within the field of Soto Zen? In my own understanding of Soto Zen specifically, what I love is the emphasis on zazen practice, of waking up in this moment. I think being fully with the environment around you is the intention of the practice. This possibility of being awake and connected in each moment, moment to moment to moment to moment. Rather than needing to go outside yourself or better yourself in some way to wake up, it’s actually a process of going inward over and over again.

How has your Zen practice informed your writing and the way you think about writing, day-to-day? In the context of Zen practice, my experience has been that because there’s so much emphasis on zazen, and on silent retreat and ritual—which are certainly very important—sometimes language gets a bad rap. As in, language is a tool to help us wake up, but this is not the practice itself.

While I think that’s certainly true, language is a very helpful and important tool. Because we’re relative bodies on this earth trying to navigate place and time and emotions and relationships. Most of us navigate language on a daily basis, and it’s such a helpful medium to connect deeper with ourselves and to others.

A curious thing about practice for me is that the more I lose a sense of permanent self, the more I identify with a fleeting self that changes moment-to-moment. That is connected to poetry as a way of processing whatever self is currently arising in that moment. So it’s not that, as a writer, as a poet, I never have a self or never have a sense of self. Rather, the process of writing, as it’s moving, helps me be open to that change all the time. Different poems or projects are representations of where a self was in that moment.

But then, the poem ends and it dies in a way and the self dies, too. And then it’s great. You get to move on to another thing.

Do you have any routines and rituals in your everyday life that influence your practice? Any specific objects or materials that you work with? As someone who habitually thinks of myself as being in my head or being in a kind of “other space,” having things that I find aesthetically pleasing around me helps me settle into my body in a physical way and sink into a place to write. I often light incense. I love making candles. I’ve become really fascinated by candle making practices across different religions and cultures and have been trying out some different waxes and stuff. I also have a lot of plants in my apartment, which I find very life-giving.

I tend to write every morning when I wake up, but I don’t write just for the sake of writing. I usually write briefly in the morning for any amount of time just to write out my dreams. I have such vivid dreams at night that I feel like it’s a process of exorcism. I need to get all this vivid language and experience that’s still in my body out onto a piece of paper, or else I feel heavy during the day. A lot of my poems start out from a place that originated as a dream.

I often feel that my poems are a bit preoccupied with place, such as where I grew up in Minnesota and Northern Iowa, even though I haven’t lived there for a long time. That kind of childhood memory or feeling is the one that often pops up in my dreams. So even if the dream is not about me being a kid in Minnesota, it helps me access that place really quickly when I’m writing.

When I’m writing, it’s usually not a great feeling [laughs]. Like, endless winter and dread and snow or something. I think that we have different parts of ourselves that, especially while sleeping, tap into a way that we felt in the past. We can feel the past in the present moment. And I think we can feel the future in the present moment, too.

***

Excerpt from What Sleeps Under Lacquer

1.

They said to get out of the car because the bridge was on fire, so we did. One of my students worked on the plans for this airport. She said she liked to imagine me drinking coffee on the floor of the terminal, the one where the bird is running loose. On other days, I question whether I’m listening to the recording of bells on the speaker, or listening. The best part of dreaming a person is, even if it’s accurate, it’s still not the way you dream when they step out of the car. Like you’ll go back to being an hour behind me, a long shadow in the grass. Like when I talk to you I feel like I’m converting you into a religion of snow.

2.

Walking around the house, careful to avoid certain patches of ice in the shadows near the middle school, my thoughts begin to blanket particular blocks, until the neighborhood becomes a series of conversations I return to, until I am suffocated by a letter of my own weaving. I imagine dissolving the fog over the lake by drawing the word sun with my mouth. Each time I draw sun, it follows into a gap where people disappear. The sentences depart and everything borrowed stays on earth like paper, incense, pine. Even the afterlife stays as snow on makeshift wooden limbs, searching for something firm to hold onto. Even the flood craves firm edges, pictures a wide, wooden hole to lie down inside and sleep.

3.

I returned to see the city drift on the horizon like a tank of gas running out in the desert, though it wasn’t the desert, it was another man-made sea, the metal sheen of emptying, it was archaic and running towards me. The lingering sound of traffic was not from the Atlantic coast. Nor was the sound that she was dreaming. Nor that she was saying something opposite to what she had initially thought. Like the sound of inches going grey, the sound of not knowing the effect of the sound as it enters your lungs and exits, the effect the sound has on a person as a whole after a long sleep, the sound spreading over a field, the sound in its new, cream-colored coat was an old sound with a new variation. Like waves breaking on a lake, or the sound of waves beginning to break, the sound of trees breaking as the wind hits them in the narrowest channels. It is natural to break in the narrowest channels. If I had previously imagined joy it did not sound like this. When it arrived I was already curled up in bed with the curtains drawn tight, so as not to hear the sound even if I knew the lake was there, hovering over my head.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.