In 2013, Richard Bryan McDaniel grew bored while recovering from a series of surgeries and decided to start writing about Zen. After having jotted down stories about Zen ancestors in a little bound book, he decided to arrange them in chronological order. “I was doing this solely to entertain myself, because I had nothing else to do,” McDaniel says.

His daughter, Madeline Elayne McDaniel—an established author who has published books under the pen name Madeline Elayne—helped McDaniel write a pitch letter, and before long, he had a publisher for his first book, Zen Masters of China: The First Step East. Eleven years later, he has interviewed more than 230 Zen teachers and priests across various lineages and published eight books—most of which document the arrival and evolution of Zen in North America (a ninth is in the works).

With titles like Cypress Trees in the Garden: The Second Generation of Zen Teaching in America; The Story of Zen; and Zen Conversations: 42 Zen Teachers Talk About the Scope of Zen Teaching and Practice in North America, McDaniel has collected a myriad of perspectives on contemporary Zen practice from assorted teaching lineages. (Full disclosure: he interviewed me for Cypress Trees.)

“The surprise to me when I entered into this was how broad ‘Zen’ as a category was,” McDaniel says. “There are various types of Zen out there, and that is what became fascinating to me.”

McDaniel’s teacher was the late Albert Low, who led the Montreal Zen Center and was a student of Roshi Philip Kapleau, the founder of Rochester Zen Center and author of The Three Pillars of Zen, a highly influential late 1960s book that introduced many Americans to Zen practice. Kapleau’s primary teacher, a Soto Zen priest named Hakuun Yasutani, cofounded the teaching lineage known as Sanbo Zen, which uses the Rinzai Zen koan curriculum and emphasizes the importance of kensho—or awakening.

“There are various types of Zen out there, and that is what became fascinating to me.”

“I was very naive when I started this process,” McDaniel says. “I assumed all Zen centers would be just like the Montreal Zen Center.” He was quickly disabused of that assumption when he visited the San Francisco Zen Center, where he witnessed the traditional Soto Zen emphasis on form and liturgy. “It felt like going from a little Indiana Quaker meeting house to the Vatican,” he says. “I began to recognize, ‘OK, there’s more to this than I understand.’ That’s basically how all the other books came about, the recognition that Zen is not one thing.”

Throughout his interviews, McDaniel also had to confront his own assumptions about what it means to be a Zen teacher. “I had an inflated sense of these people before I met them,” McDaniel says. “What I discovered was that I was met with great graciousness. Every single one of them was somebody I would happily drink a beer with and talk about anything other than Zen. They were all willing to open up. They were all willing to speak to me.”

McDaniel’s path to Zen practice started in northwest Indiana, where his father, a contractor, assigned him to work on an aluminum siding crew when he was in fifth grade. He hadn’t planned on going to college and assumed he would soon be sent to Vietnam. “One of the kids on my siding crew was drafted. He was dead [within] less than six months,” he says. He enrolled at St. Joseph’s College in Rensselaer, Indiana, where philosophy and literature courses awakened a love of learning. After two years, he transferred to a more affordable program at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

A card-carrying member of the 1960s counterculture movement (which continued well into the early 1970s), McDaniel frequently used mescaline, the active ingredient in peyote, and early one morning, in the wake of a fraught emotional encounter, he experienced a spontaneous awakening. “The only way I can describe it is that I was so exhausted at that moment that I could no longer maintain the effort of being Rick any longer—I let it drop,” McDaniel says. “It was like you’re driving along on a highway, with a dial radio, and you move the dial a little bit and the signal has always been there… It was an absolute overwhelming sense of ‘the universe is love.’ ”

McDaniel knew little of Buddhism at the time. As he tried to make sense of his experience, friends pointed him to the work of Anthony de Mello, a Jesuit priest who taught a spiritual path that blended Christianity with elements of his Indian heritage. That led McDaniel to the Montreal Zen Center, where he became Albert Low’s student. Early in McDaniel’spractice, Low authorized him to lead a sitting group in Fredericton, which he continues to do.

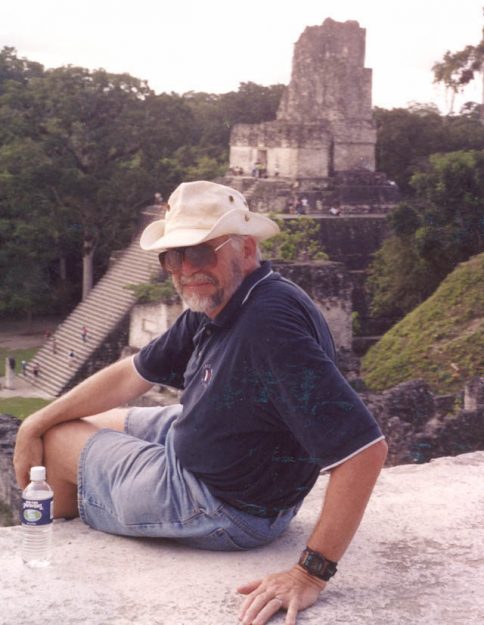

McDaniel eventually earned a PhD in literature and taught for a few years before beginning his twenty-seven-year career as an international development officer with the YMCA in Canada. In 2013, a modest inheritance allowed McDaniel to undertake a spiritual pilgrimage, when he embarked on an epic road trip to some of the major Zen centers across the United States, resulting in Zen Conversations. He says his post-retirement book-writing career has yielded several insights into the state of North American Zen practice.

For one thing, practice styles vary considerably. “If you’re a Roman Catholic and you go to Mass in Ottawa, Oaxaca, or Venice, you expect the experience to be pretty much the same thing,” he says. “If you’re a Zen practitioner, you can go to three different centers in your own town and they [won’t] have anything in common at all.”

McDaniel maintains that a major point of divergence among North American Zen practitioners revolves around the significance of kensho. Rinzai and Sanbo Zen teachers consider kensho the essential point of practice, whereas Soto teachers seldom mention it. The difference could also be described as a contrasting focus on the qualities of prajna and karuna—wisdom and compassion.

He adds that most contemporary Soto teachers “throw out the idea that there’s anything to be ‘attained,’ but they’ll talk about ‘maturity.’ Part of [that] ‘maturing’ is in your relationships with others.”

Today’s practice forms also tend to be less rigorous than in the 1960s and 1970s, when early Japanese teachers first came to the West, McDaniel says. “Zen, today, would be seen as pretty thin by people like Kapleau, when compared with the way in which Zen was seen in the past.”

The hunger for enlightenment has, in many cases, been replaced by the desire to alleviate suffering, he says. “When I ask, ‘Why do people come to your centers?’ [teachers] almost always talk about things like stress… Part of that is the sense that there’s a need for finding a way to discover compassion in our lives. So that’s become a really central issue in new [American] Zen.”

The shift in teaching also reflects a process in which Western Zen teachers, most of whom live lay lifestyles, have integrated their insight into their own lives and relationships, he says.

“This is my guess: there was originally [a] sense that people need to have these (awakening) experiences [to make] the teaching valid,” McDaniel says. “[But many] did [this at] the cost of [a] sense of compassion. But as they lived their lives, they realized, ‘This is not actually helping me engage with other people.’ So there was, I think, a great resurgence or [recovery] of karuna.”

While North American Zen continues to evolve, McDaniel believes that—within these many differing practices—a unique method for addressing perennial questions still exists while offering a way to live a richer, more integrated life. “You can use those qualities that are part of Zen training [and apply them] to a number of different ends,” he says. “I don’t think that’s going anywhere. There will always be Zen.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.