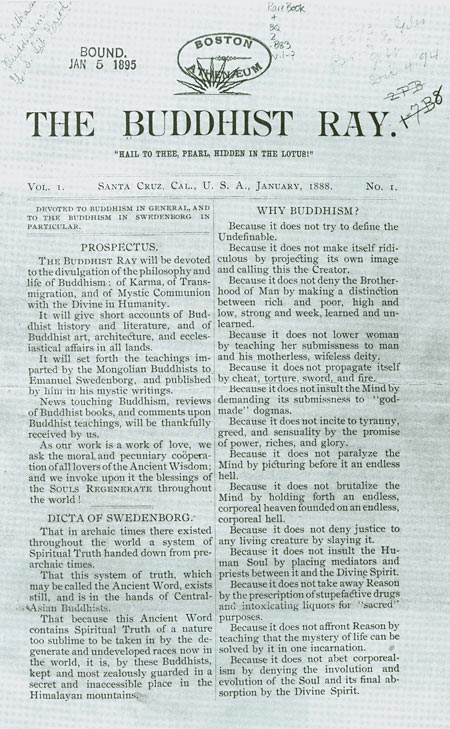

The United States produced its fair share of cranky religious characters throughout the 19th century, but the self-named Philangi Dasa was surely one of the most original. In 1887 he published The Buddhist Ray, the first Buddhist journal in the United States, and announced that it was “the first Buddhist baby born in Christendom.”

Dasa vowed that for seven years he would publish this “Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Lord Buddha’s Doctrine of Enlightenment,” and he accomplished his mission with zealous dedication from the mountains above Santa Cruz. He named his cabin Buddharay and championed his beliefs passionately from this remote outpost. Delivering his unorthodox views with self-righteous conviction, he offended readers regularly but his outspoken brand of sincerity made the The Buddhist Ray one of the liveliest Buddhist journals ever.

Born Herman C. Vetterling in Sweden in 1849, he emigrated to the United States (exact date unknown) and then became a follower of the Swedish mystic Swedenborg. After studying for the ministry, he served Swedenborgian communities in the Midwest for four years until scandal marred his clergical career. In July, 1881, The Detroit Post and Tribune reported that fellow passengers on a steamer from Alaska had accused Vetterling of having “taken improper liberties” with an eight-year-old American girl and a twenty-year-old Chinese woman. Neither proven nor ever brought to trial, these allegations remain one of several mysteries that surround his reputation.

Three years later, Vetterling joined the Theosophical Society in which identification with Buddhism was common; and wishing to make a fresh start, he moved to California. Using his pseudonym, he wrote Swedenborg the Buddhist, or The Higher Swedenborgianism: Its Secrets and Tibhetan Origins. With characteristic enthusiasm for his new-found faith, Dasa claimed for Swedenborg a similar allegiance, suggesting that “hidden under Judaic-Christian names, phrases, and symbols, and scattered throughout dreary, dogmatic, and soporific octavos, are pure, precious blessed truths of Buddhism.” Undaunted by the outrage this provoked among the Swedenborgians, Dasa continued his sure-footed and somewhat imperialistic raids into allied ideologies in his monthly periodical.

Drawn to Buddhism in part by its record for tolerance, Dasa himself could not let an opposing view stand without comment. When The Buddhist Ray published an excerpt by the American Spiritualist Andrew Davis that hinted that Buddha’s doctrines were less significant than his social reforms, Dasa added: “A radical mistake—Ed.” Another of his editorial condemnations read: “We are confident that when Mr. Davis penned this, he knew very little, if anything, about the thoughts and ordinances of our Lord—Ed.”

To the suggestion that he make public promotional appearances for the Buddhist cause, Dasa explained that this was impossible, for, among other reasons, “we have no mahatmic credentials from the Himalayas, a serious obstacle indeed.”

What little we know about Dasa reveals the ambiguity and ambivalence that continues to attend issues of accreditation. His interpretations lack both the restraints of orthodoxy and the subtleties of Asian expression. His was an imagination inspired by the contagious spirit of an American frontier that summoned its ragged idealists toward territories unknown, inside and out. His deepest concerns paralleled those of many American Buddhists today: vegetarianism, homeopathy, women’s rights and the humane treatment of animals. And his pioneering reflections on the essence of Buddhism, the authenticity of intellectual and practical innovations, and the limits of cultural adaptation are very much alive in the current discussions of Buddhism in North America.

Co-authored by Thomas A. Tweed, whose book, The American Encounter with Buddhism, 1844-1912 will be published by Indiana University Press next year, and Helen Tworkov, editor of Tricycle.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.