“We’re moving to America,” my father said with finality.

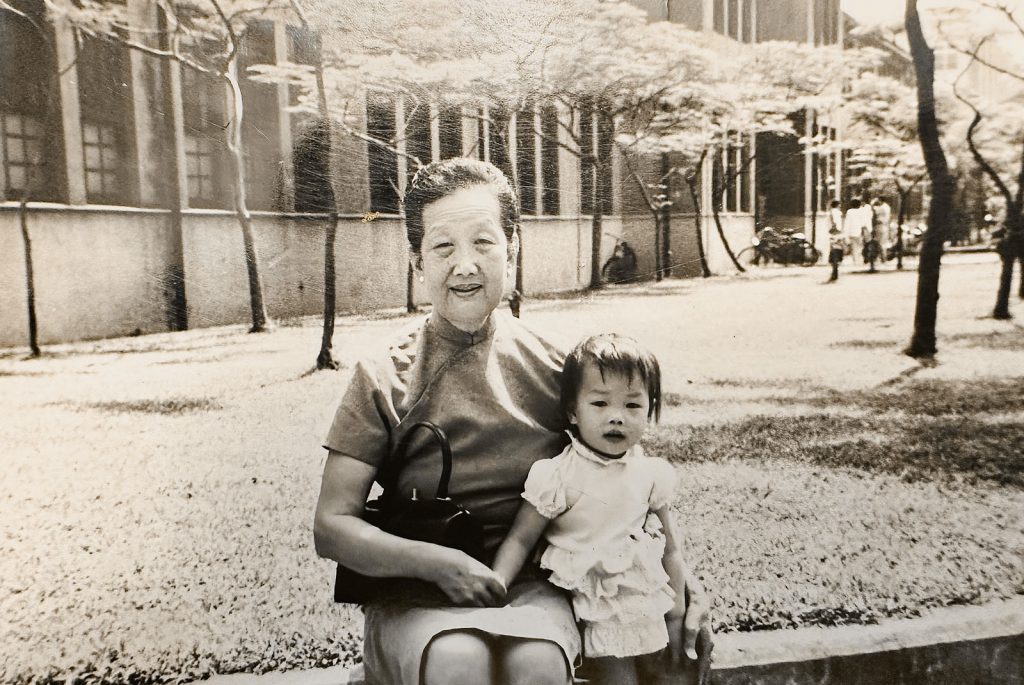

She took the news silently, my grandmother. We were gathered around her in the living room of our Taipei apartment. She wore her customary beige cheongsam dress, her hair neatly gathered in a bun at the nape of her neck as she sat in an armchair. Slowly she nodded, as a glimmer started collecting at the edge of one downcast eye, a welling repository of the unspoken.

We were leaving her.

For the first nine years of my life, my parents, sister, and I lived with my grandparents. The flavors of childhood made a deep impression. Every week, I went hand in hand with my grandmother to the street market to pick up vegetables and visit local food stalls for snacks like youtiao—long strips of dough, fried to an airy crispiness—the light greasy layers crackling into a shower of golden salty fragments as you bit into them and dunked them into a bowl of steaming sweet soy milk. Then there was the oyster thread soup at the night market and my first taste of cilantro—what a shock to the taste buds. The piquant grassiness collided with the saltiness of the glass noodles, and the contrast dumbfounded me for hours. My grandmother often cooked comfort foods: steamed minced pork patty, which crumbled into savory morsels atop fluffy rice, and a whole chicken stewed in the big metal rice cooker with so much wine that my face flushed red when I sipped a bowl of the hot broth.

We lived on the third floor of an apartment complex. My grandparents’ room was dark and cool, smelling of antique wood. I knew that in the tall dark dresser in the corner they kept a jar of spare change, from which I would occasionally fish out a few coins when no one was looking. I would then buy preserved plum patties from the local snack shop, sucking on the little sour and sweet discs on my way home from school.

It was in the living room where my father first broke the news of our departure for the United States. She did not argue or fight with my parents. It was a foregone conclusion. They had made up their minds that they were going to go. They were simply telling her what was going to happen. I watched as a big glassy tear rolled slowly down the soft folds of her cheek.

And so, we moved to southern California. We stayed with my mother’s college friend at her home in the San Gabriel Valley, a suburb about thirty miles east of downtown Los Angeles. Her family lived in a one-story ranch-style house framed by big leafy palms, nestled in a quiet cul-de-sac.

Every day brought interesting lessons about our new home. The spacious kitchen held particular fascination, with its strange electric stoves that lit up mesmerizingly red. Despite warnings, I couldn’t resist touching the glowing coil, only to draw my hand back in pain, papery white blisters welling up on my fingertips. Exploring the refrigerator, I discovered some orange squares stacked neatly in a side compartment, each one wrapped in cellophane. What were these crayon-colored flaps doing in the refrigerator? Can you eat them? I had never seen anything so mysterious. I gingerly unwrapped one of the squares. It was soft and pliant in my hand. Slowly I held it up to my lips and took a nibble. My face immediately bunched up. It was the strangest taste I had ever encountered—waxy, curdled, and artificial like rubber. I spit it out. This was my first introduction to American food.

The immigrant acclimation process entails constant trial and error, making mistakes and absorbing the results, then shape-shifting. We quickly picked up the ways of our new home and adapted to life in suburban southern California in the eighties—every day there was something to figure out: how to pronounce l’s and r’s, hit the tetherball higher than your opponent’s head, strike that magical balance on a bicycle without falling into thorny bushes, roller-skate backwards on asphalt, and choose your favorite Charlie’s Angel.

When my parents had saved up enough to buy a house, we moved into a ranch-style one-story house right up the hill from the Puente Hills Mall (where they filmed Back to the Future). Weekdays after school were spent either at my Latina gal pal’s house down the street, listening to Journey in her garage, or loitering at the mall, where we got our ears pierced while sipping on an Orange Julius. Who wants to eat Chinese food when you can have a quarter pounder, with that gooey melted American cheese?

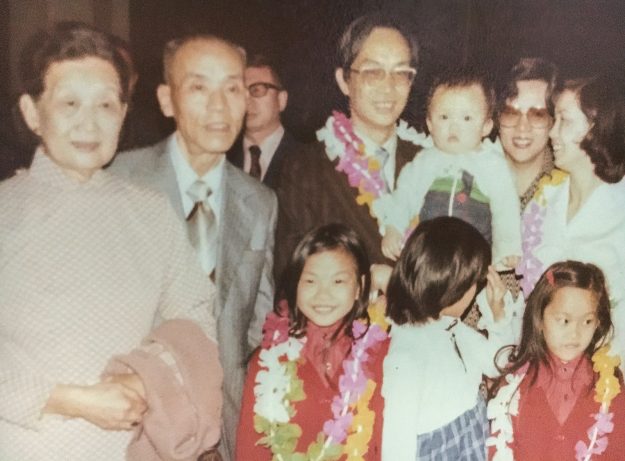

By the time I saw my grandmother again, five years later, I was a full-fledged American teenager.

After my grandfather passed away, she came to America to live with us. She still wore her customary cheongsam dresses and styled her hair in a bun. She still watched Chinese opera on TV and used an abacus to calculate.

I was in junior high, trying to fit into a world of which she had no understanding. Daily battles with mean girls at school filled me with dread. Whenever I went to my locker, they would be there. They pushed me against my locker door so that the rusty metal edges pressed into my skin as I tried to switch out my books, causing little pink welts on my arm that disappeared soon enough, but left indelible impressions on my young mind.

I now stood eye to eye with my grandmother, and no longer understood her heavy Fukinese-accented Chinese. Time and distant shores had created a divide—we were foreigners to each other. The loss of culture and basic communication was painfully evident, and there was no hiding from the shame that I felt. To avoid the awkwardness, I kept talking to a minimum, and we lived side by side, falling into the family routine. School, dinner, church on Sundays, repeat.

Two years of relative calm passed.

One afternoon after school, I heard a cry from the next room. There was no one else at home, and I walked into my grandmother’s room to find her shaking violently on the bed. I stood rigid at the edge of the bed, frozen in shock. Her whole body quaked uncontrollably, from head to toe. She lifted up one trembling hand. What should I do? What shouldn’t I do? She was trying to say something between the clattering of her teeth. “Bu…,” she said—“no,” in Chinese. She’s saying no? She continued, “Bu…bu…bu…yao…yao”—the second word means want. She doesn’t want…? “Bu…yao…pa.” The last word completed the sentence. “Don’t be afraid,” she said. “Bu…yao…pa.” She was addressing me and telling me not to be afraid!

She gestured to the dressing table, I ran and grabbed a bottle of medicine and opened it, and put some small pills in her quaking palm. She shakily brought them to her mouth and swallowed them. She closed her eyes, and laid her head down on the pillows, exhausted, her tremors slowly calming down. I silently returned to my room, shaken to the core. I don’t remember anything that happened immediately after that, whether I called my parents, how she entered the hospital, how she got her diagnosis of colon cancer.

We visited her in the hospital. We hugged her and told her we loved her. And a few months later, she was gone.

For decades, I was haunted by that moment in her room. Why hadn’t I been stronger? Why hadn’t I comforted her? Why hadn’t I crawled into the bed with her and held her until the shaking stopped? There must be something wrong with me. My heart is not big enough. It was the culmination of the guilt over the loss of our closeness. The shame burned through the years, my inability to act my albatross. No matter how much I achieved as an adult, I could never get away from that one failure seared into my heart.

It took a life crisis in my 30s to reset this deeply ingrained narrative. My marriage was falling apart, and with no spiritual practice, I was floundering. A friend started meditating at the Los Angeles Compassionate Heart Sangha, and I tagged along out of pure curiosity. Even though I spent the entire first meditation focused on not sneezing, I somehow felt relieved to be there. I began attending every Sunday. I sat and breathed with others who became a second family. We breathed together through my divorce as life crumbled around me, and we breathed together as I slowly rebuilt my life, healing and emerging on the other side of the tunnel, softer and with more self-knowledge.

One ordinary day during the pandemic lockdown, I was scrolling through Facebook and saw a post by Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzberg. By this time, I had been meditating for years. The post said:

As we construct our identities, we tend to reinforce certain interpretations of our experiences, such as, “No one was there for me, so I must be unlovable.” These interpretations become ingrained in our minds and validated by the heated reactions of our bodies. And so they begin to define us. We forget that we’re constantly changing and that we have the power to make and remake the story of who we are. But when we do remember, the results can be dramatic and turn our lives around.

Suddenly, in a flash, coming out of nowhere and without trying, the memory of me as a 14-year-old frozen in fear in front of my grandmother on the bed played out before me. Only this time, I was an adult observer, watching the scene as though it was a movie flashing on the screen. And it came to me. The real story. “Bu yao pa—don’t be afraid.” The real meaning to come out of this moment, which was overshadowed by my shame, was that my grandmother loved me. She loved me so much that even though she was in severe physical pain, even though she didn’t know what was happening to her body, what she thought about first was me, her granddaughter, who was just a terrified kid who had never encountered sickness and death before. And her first instinct, despite the violent illness that was shaking her body from the inside out, was to try to calm me down.

That is the beautiful heart of the story, the vast love of a grandmother, beyond physical pain, that bridged the gap between two shores. This realization out of the blue broke down the ramparts and the tears fell freely and completely, dissolving the knot inside of me, flooding out the shame and replacing it with a new understanding.

Buddhist teacher Tara Brach says, “The more we bring tenderness to the life right here, the more the sense of the self actually starts dissolving.” Meditation practice helped me to observe my inner dialogue and how harsh it was. Only when I became kinder to myself was I able to loosen the grip around the identity I had built up. With each breath, the lid slowly came off the pressure valve, allowing me to free up space inside and see the world anew, as it really was.

Sometimes our beliefs about ourselves get so ingrained that they block us from seeing anything else that’s there, and we spend years trying to get away from it. The real story is much bigger than we know. How can we bring tenderness to that story, and start dissolving the false stories we’re telling ourselves?

What stories in your life need to be retold, with tenderness?

I recently planted cilantro in my garden. I add it to the minced steamed pork and stewed chicken broth that I make to recapture my childhood. I add it to salsa and guacamole, to chimichurri, to tart green salads, even to burgers in the multicultural milieu that is my life in America. I love all of the fragments coming together, all that’s here, the luster and the shadow, the gladness and the suffering of the world and in me, and, ultimately, the peace that comes from the grandmother in my heart who says:

Bu yao pa.

Don’t be afraid.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.