When he was a graduate neuroscience student, Jay Sanguinetti attended a two-day retreat in 2014 with Shinzen Young, a prominent meditation teacher who describes his unique blend of Theravada and Mahayana techniques as “algorithmic”—meaning he offers students a very precise set of “if, then” instructions for navigating their inner experience.

“Shinzen’s retreat was the first retreat I had been to in five or six years,” Sanguinetti recalls. “It was so radically different than anything I had experienced up until that point.” Afterward, he approached Young and told him that he was researching the effects of ultrasound stimulation of the brain.

“I pitched it to Shinzen: ‘What about ultrasounding the brain and trying to teach people meditation?’” Sanguinetti recalls. “Shinzen had the responsible answer, which is, ‘It’s not ready, we need to learn more about it.’”

But in 2017 the pair reconnected—and now Young was onboard. Since then, he and Sanguinetti, associate director of the University of Arizona’s Center for Consciousness Studies in Tucson, have been running studies to determine whether exposing meditators’ brains to targeted ultrasound energy can help them quiet their inner chatter and enhance feelings of equanimity, or an internal steadiness.

The pair, who have raised $480,000 in funding, mostly from grants or private foundations like the Evolve Foundation, have an audacious plan. They hope to translate their research into an app-based artificial intelligence-driven technology that they believe holds the potential to transform society.

“If we can enhance baseline levels of equanimity, that might serve as the basis for accelerating the learning of mindfulness skills,” Sanguinetti says. “Can we measure that elevation? Is it safe to move people in that direction? And if that’s true, does that help people learn mindfulness skills quicker? And the last question is, ‘Is that good for behavior in the world’?”

Young puts it more succinctly. They are in the business of “democratizing enlightenment.”

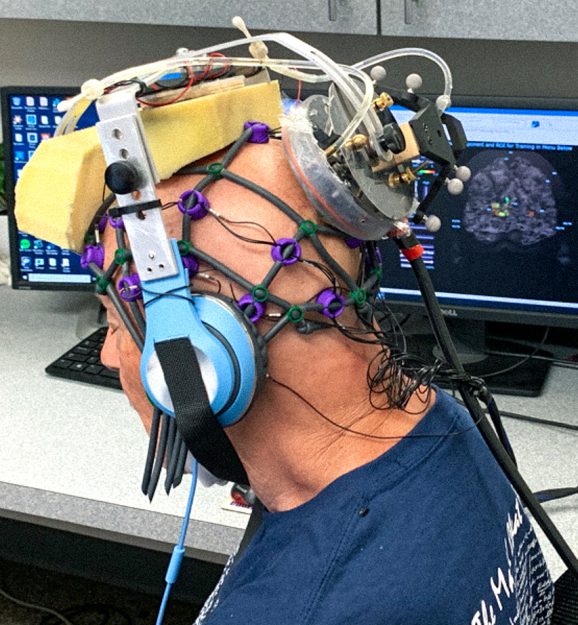

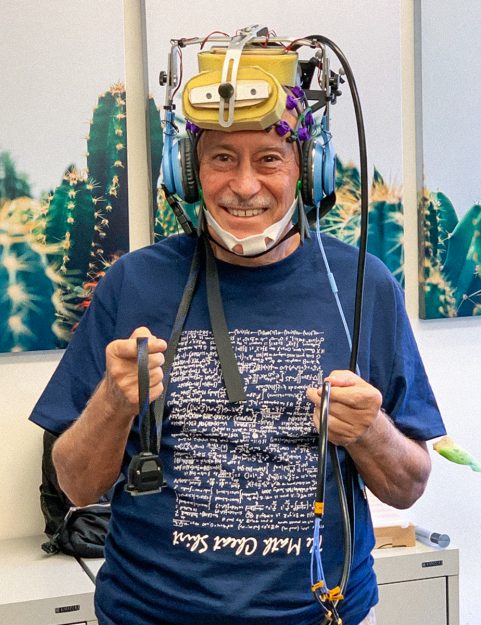

The project follows standard neuroscience research protocols. In the lab, study subjects (novices as well as experienced meditators), don something that looks like a hairnet studded with ultrasonic transducers. Over a period of five or 10 minutes, they receive intermittent pulses of ultrasound energy. Ultrasound frequencies are far above the threshold of human hearing, so the test subjects feel no sensations, and because this is a placebo-controlled study, some people receive no stimulation at all.

The project follows standard neuroscience research protocols. In the lab, study subjects (novices as well as experienced meditators), don something that looks like a hairnet studded with ultrasonic transducers. Over a period of five or 10 minutes, they receive intermittent pulses of ultrasound energy. Ultrasound frequencies are far above the threshold of human hearing, so the test subjects feel no sensations, and because this is a placebo-controlled study, some people receive no stimulation at all.

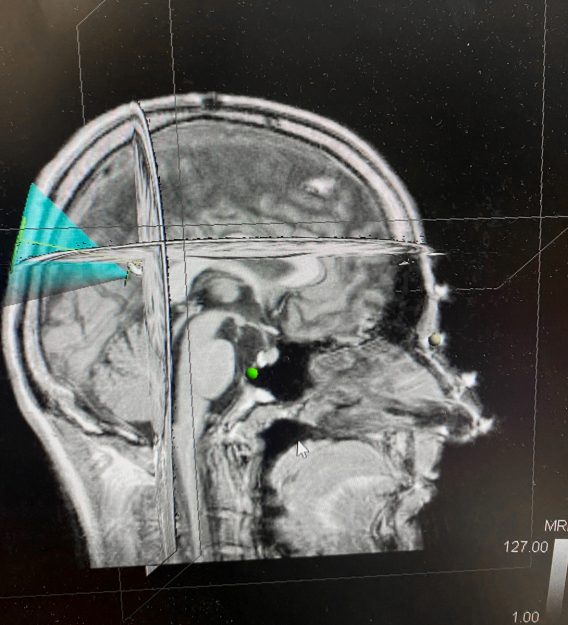

Participants may also undergo ultrasound stimulation while lying in an MRI scanner that enables the researchers to gauge how different brain regions respond to the intervention. “The biggest brain and subjective reports are at about 20 minutes post-ultrasound,” Sanguinetti says. “So there’s some change in the way the brain regions are talking to each other.”

Ultrasound is a relative latecomer to the field of noninvasive brain stimulation, Sanguinetti says. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation—which sends a small amount of electric current through the skull—have been extensively studied as treatments for depression and other psychiatric illnesses. But in the past few years Sanguinetti and others have established that ultrasound is safe.

“You can think about it as an acoustic field that’s focused into something like a pencil shape—it’s really long and thin,” he says. A technical challenge is that the skull tends to distort the field, so researchers have to adjust the beam to ensure it’s aimed at the right brain structure. “Once you do, you get millimeter resolution,” Sanguinetti says. “You can pretty much target any depth in the brain, which is a huge advantage over any other noninvasive brain stimulation.”

The primary target is the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), a region deep in the brain that is massively connected with other structures and is associated with the default mode network—active during daydreaming and mind-wandering. Young and Sanguinetti theorize that the ultrasound energy mutes activity in the PCC in much the same way meditation tames the “monkey mind.”

For Young, this maps perfectly onto the Buddhist paradigm.

“The basic model that we’re using is that the ‘okayness’ is already there,” he says. “There’s a primordial face that everyone has before anything is born. It’s always there. The basic Buddhist model could be interpreted as, ‘All you have to do is stop doing something to be OK.’ So as you’re going into equanimity, you’re letting go of grasping. You actually stop holding on and interfering with the natural flow of the senses.”

Young, who in 1970 ordained as a monk in a Shingon Buddhist monastery while a graduate student in Japan, emphasizes that the technology he and Sanguinetti are developing is intended to help people overcome obstacles to meditation and move more quickly along the path to awakening.

“We’re not replacing enlightenment,” he says. “We’re not replacing getting over the self and we’re not replacing refining the self. And we’re not negating the need for bodhisattva-type service. We’re not asking anybody to believe that: we’re only asking them to believe that concentration power, sensory clarity, and equanimity are trainable and relevant to human happiness at all levels.”

While the technology could make meditation more accessible for novices, “we’re not saying we’re going to make it easy and quick,” he says. “What we mean by that is no watering down of the really good stuff in terms of the dimensions that we might call liberation on the one hand and character development on the other.”

Ultrasound’s apparent effect on consciousness sits squarely within a Buddhist framework, Young contends. “We’re thinking that equanimity is the centerpiece, rather than concentration or even clarity. Because it’s core Buddhism, it’s the Four Noble Truths, it’s the letting go of the push and pull on the flow of the senses. We call it equanimity: the Buddha called it ‘letting go of craving and aversion.’ That’s the kleshas.”

Experienced meditators report significant effects after undergoing the ultrasound sessions, Sanguinetti says.

“Some people said, ‘This is like a week of retreat, and my baseline equanimity and baseline concentration is enhanced to what it would be like after five days on retreat.’ We got really excited, but with the understanding that these long-term meditators had a lot of prior experience, and this all could have been interacting with the placebo effect in some ways that’s hard to disentangle.”

The study was paused due to the pandemic, but it has since resumed, this time including less-experienced meditators—and those with zero experience. “We’re targeting those brain networks, first asking the basic question: Can we modulate the network we’re interested in?” Sanguinetti says. “It seems like we can. We’ve got these beautiful network changes in the default mode network.”

Adds Young, “We get these equanimity-related reports from the participants without prompting. They don’t know that we’re looking into anything related to meditation—we’re just some mad scientists that want to put energy into their brain. They on their own report some very meditation-like things.”

The pair started out by experimenting on themselves. “I have a principle in the lab that I won’t do anything on anybody else in terms of brain stimulation, unless I do it on myself,” Sanguinetti says.

He later put the procedure to the test during a 15-week online meditation retreat. “Four weeks in, I started four weeks of ultrasound,” he says. “The general effect was, within the first week, an extreme quieting of both inner and external space. The inner space became much stiller than I was able to accomplish just by sitting for 45 minutes every day. With the PCC ultrasound, it was within the first five minutes.”

Young helped Sanguinetti contextualize some of what unfolded as his conscious mind became very still. “My attention could sort of hone in very quickly on things that were occurring and I could see the way emotion was connected to visual thought,” Sanguinetti says. “But I’d never seen the unconscious mind get still.”

Equanimity was significantly elevated, he says. “I felt like I had this superpower where, if I stabilized my attention and focused—if I just increased my concentration a little bit—that I could blast into equanimity. That started occurring when I was off the pillow, when I was walking in the world, when I was giving talks. Those levels of equanimity were just present.”

Young, whose lifelong love of mathematics and science informs his style of Buddhist teaching, has an expansive vision for the future of app-driven meditation instruction, which he expects will help students realize his “Periodic Table of Happiness Elements,” a grid of twenty factors leading to greater fulfillment and less suffering.

“We want to marry [the ultrasound stimulation] to interactive apps that incorporate really effective AI, then use humans as the safety net underneath the apps,” he says. “We want to bring that on and couple it in one device, where the interactive training with the app and the neuromodulation come together. You might be able to buy it from Amazon, but that would be a good thing, if it delivers the goods and does relatively little harm.”

For some, the prospect of a powerful new brain stimulation technology might conjure up nightmarish scenarios. What if someone amped up the dose and caused brain injury? What if an employer (or the government) forced people to undergo ultrasound treatments?

The risks are real, Young acknowledges.

“This is scary shit—really serious,” he says. “But if people like us aren’t the first to market with this, it’s going to be someone’s skunk lab with some very limited agenda for someone who cares about power. We’ve thought it through. That’s why people like me and Jay have a moral responsibility to do this research, because we do it in the open and we have a happiness grid that says these are the better angels, and this is what we’re working toward with this technology.”

However scary the project may be, it’s clear that for Young, it is a dream come true.

“It’s like I’m eight years old, and I get every day to speed dial a senior, cutting-edge research scientist doing something important in the world that few people can even understand,” he says. “Why are they even letting me in the room here? This is so much fun for a little kid.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.