Introduction

This web series on the Lotus Sutra’s seven parables invites the reader to contemplate these parables through their own inter-personal experience, rather than stating another dogmatic, literal truth.

Religious texts are often viewed as moldy old tomes disconnected from current times and considered meaningless and irrelevant. The jewels of their insights are lost in their obscure archaic language from ancient cultures, vastly different from what we’re used to in today’s 21st century. When they are presented as the literal truth and exact words of their prophet, founder, or god-head, they are even less relevant and accessible. It’s easy to understand why many turn away from these great works of written art, considering them meaningless and irrelevant.

Truly great religious and philosophical works use mythopoetic storytelling and parables to explore complex feelings, emotions, thoughts, and ideas that defy intellectual understanding. This form of storytelling invites the reader to pursue their own experience and relationship with these ideas as a means of self-understanding and awakening.

This web series will share these parables as a portal into one’s own personal and direct experience with the sublime, wondrous, and mysterious nature of the universe. It will invite readers to ask themselves, “What does this work say to me? How does it inspire me to live my life in a wholesome, wise, compassionate manner? How can I find meaning and purpose in my life?”

The Buddha said many times that nirvana can’t be comprehended or grasped, and that our sixth sense organ, the discriminating consciousness, can be a fetter to awakening. The Buddha taught the Four Reliances in both the Vimalakirti Sutra and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra:

“Rely on the Dharma, not upon the person;

Rely on the meaning, not upon the words;

Rely on wisdom, not upon discriminative consciousness;

Rely on the definitive meaning, not upon the provisional meaning.”

This web series shares the Lotus Sutra’s parables using this time-honored interpersonal, introspective, and contemplative approach, inviting the reader to open their heart/mind to a deeper personal experience through direct experience of the sublime by reading the parable—a mythopoetic story—and then sitting or chanting with it in calm abiding insight, diving deep into the metaphor, making it one’s own, and then rising back to the provisional with a whole new perspective.

Reading is one of the Five Practices the Buddha taught in the Lotus Sutra:

embrace,

read,

recite,

share,

copy.

Reading these parables is like viewing a multifaceted jewel. What you see depends on how you are holding the jewel, where you are looking into it, what you are feeling at that moment, and what the lighting is when looking. A near infinite number of views is possible, and they are constantly changing. Each contemplative meditative journey can and will be different, offering insights that change and vary according to one’s mental state and situation. This interpersonal exploration is a constantly unfolding and enlightening process flow of experience.

Instead of being another moldy old tome, these parables can be a friend and companion—a continual source of insight and inspiration, like a compass needle that always points north, regardless of the mountains, plains, and rivers on a map.

Background of the Lotus Sutra

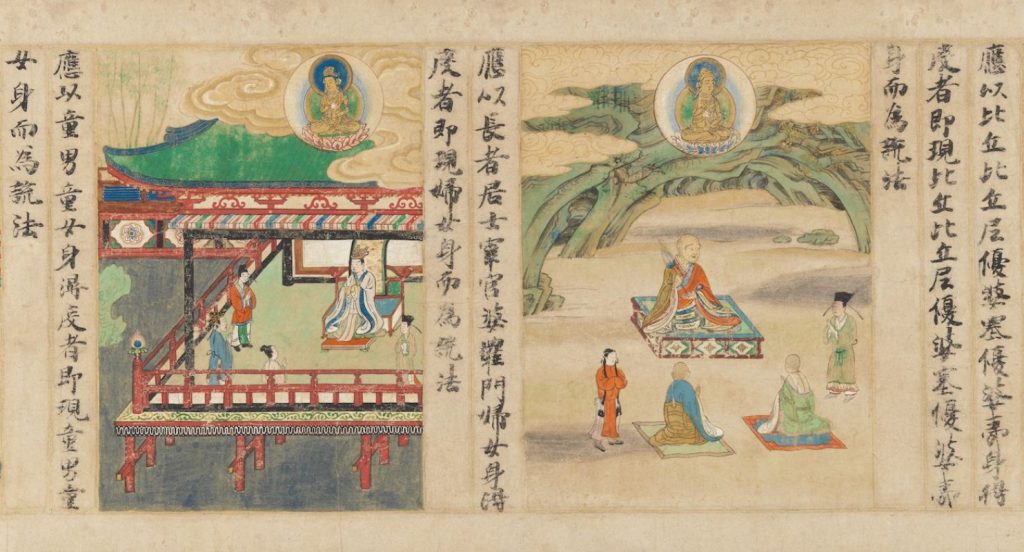

The Lotus Sutra is one of the world’s great religious texts. It is a Mahayana sutra first discovered in the 1st Century BCE in the city of Kashgar, located within the Kushan Empire, a region in Central Asia, now China. Kashgar is one of the westernmost cities of China, located near China’s border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Kashgar was a strategically important city on the Silk Road between China, the Middle East, and Europe for over 2,000 years. It is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. There is solid evidence that the Lotus Sutra, like all Mahayana sutras, was deeply influenced by the convergence of ideas and philosophies from the mixing of cultures and ideas, East and West.

The Lotus Sutra’s original Sanskrit name is Saddharma Pundarika Sutra. Chinese (妙法蓮華經): Miàofǎ Liánhuá jīng, Japanese: Myoho Renge Kyo, and English: Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wondrous Dharma.

The most common version today is based on Kumarajiva’s Chinese translation from the Sanskrit, completed in 406 CE. The Lotus Sutra was compiled in three sections: Chapters 2–9 during the ~1st Century BCE; Chapters 1, 10–22 (except for 12) ~100 CE; and Chapters 12, 23–28 150 CE. That’s a span of 250 years!

Some question the legitimacy and progeny of the Lotus Sutra as writings of others rather than Shakyamuni Buddha. Others claim it is the ultimate words of the Buddha. This series will not address this ancient debate. Frankly, we must be honest with ourselves that we will never know. I personally believe that engaging in such religious polemics is a fetter and barrier to awakening and to be avoided. I believe that everything the Buddha taught was skillful means intended to invite the practitioner to have a direct experience with reality themselves.

The beauty of Buddhism is that because the Buddha was able to awaken to the true nature of reality and become “enlightened,” then we too can awaken and share the same experience. Logically then, because Buddhism works for all people equally, then everyone’s awakened experience is an authentic, true, and real expression and manifestation of the true nature of reality. It then doesn’t matter who or when someone actually spoke these words or wrote them down. Whether or not the Buddha spoke the exact words in the Pali Canon or Mahayana sutras is irrelevant. Buddhism is a living, breathing, continually evolving flow of the dharma, all the suttas, sutras, and commentaries are crowd-sourced from the collective wisdom of generations of men and women who dove deep into meditation and brought back their experiences and then wrote them down so others can share in the experience.

The Lotus Sutra’s two great contributions to the collective works of Buddhism are, 1) Prediction of Buddhahood for practitioners of the Two Vehicles (arhats and pratyekabuddhas), evil people, non-believers, women and animals, and 2) the life of a buddha has no beginning and no ending.

The Lotus Sutra is so encouraging because it states emphatically that everyone will become a buddha without exception, and the life of a buddha is timeless and boundless, manifesting continuously outside of space time. This is a profoundly more positive, inclusive, and holistic way of expressing emptiness.

This web series will present the Lotus Sutra’s seven famous (and two not-so-famous) parables in a modern context. It will explore their meaning from an inter-personal, introspective, and contemplative point of view, rather than the traditional doctrinal dogmatic one. For instance, the parable of the wealthy father and poor son shares two themes, 1) one’s self-perception and image create limitations and barriers to living a wholesome meaningful life of purpose, and 2) the very compassionate and tender way it shows us that no one is perfect, that even the Buddha was a human being and made mistakes when he taught.

The nine parables this web series will present are:

- Burning House – Chapter Three

- Wealthy Father and Poor Son – Chapter Four

- Medicinal Herbs (Rain of the Dharma) – Chapter Five

- Magic City – Chapter Seven

- Jewel in the Robe – Chapter Eight

- Precious Pearl in the Topknot – Chapter Fourteen

- Physician – Chapter Sixteen

- Potter – Chapter Five

- Digging a well – Chapter Ten Preacher of the Dharma

See you next month when we dive into the Burning House!

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.