Burma is home to around 60,000 Buddhist nuns. They have taken monastic vows, shaved their heads, and donned robes. Yet these thilashin are not equal to their Theravadan Buddhist male counterparts.

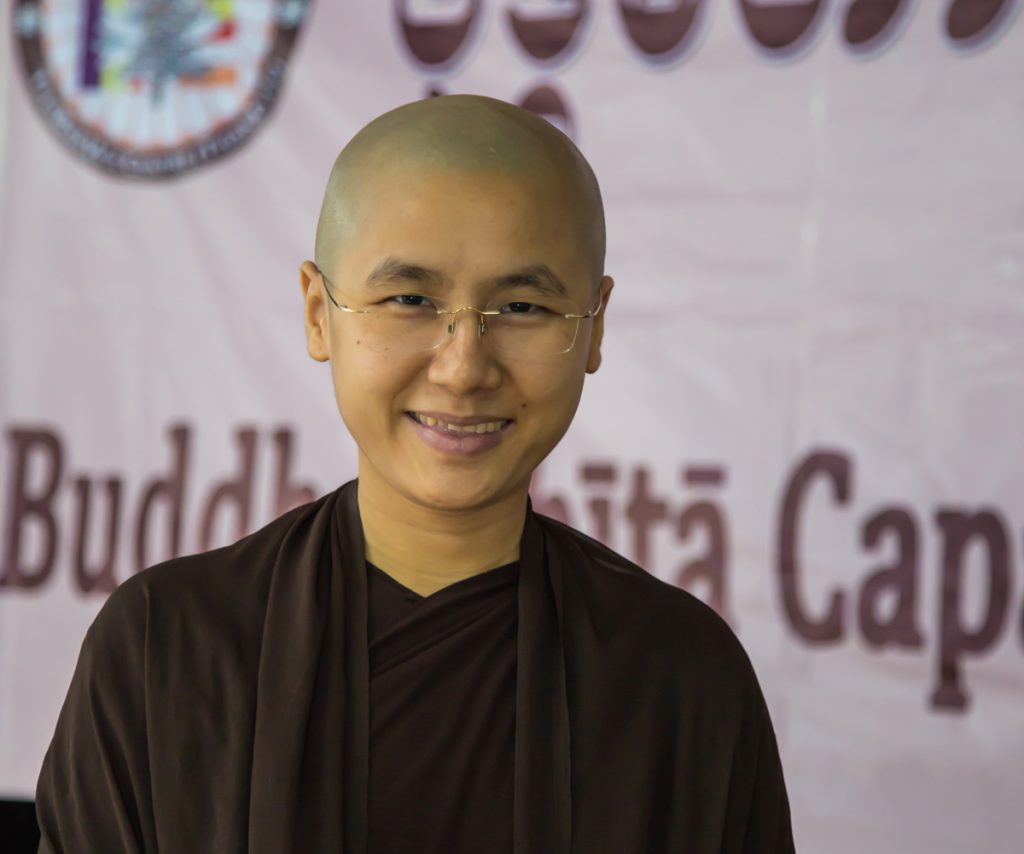

In this deeply religious country, people give up their bus seats to monks, bow to them on the streets, and give them daily alms. Nuns, however, are forbidden from formally teaching the dharma and scarcely merit a backward glance. But Ketu Mala, a well-known Burmese nun, is breaking the mold. “Let’s face it,” the 36-year-old nun says in a soft voice, speaking partly in English and partly in Burmese. “Burma has a male-dominated, patriarchal society, which means religious life is also dominated by men. The patriarchy is deep-rooted here.”

Founder of the Dhamma School Foundation, Keta Mala has had remarkable success in bringing Buddhist teachings into mainstream education for Burmese boys and girls. Her organization has established a network of thousands of schools across the country, reaching more than half a million pupils. She has caught the attention of former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, who met with her recently, and she gives popular religious talks worldwide.

Ketu Mala recalls first experiencing gender injustice when she was about 13 years old. Her uncle and cousin were being ordained as monks in Mawlamyine, her hometown, in southern Burma. But Ketu Mala and the women in her family were not allowed to enter the part of the temple where the ordination was taking place.

“For the first time I am feeling different from the males,” she said, recalling a sign that barred her entry. “And I am thinking, ‘Why can a man do that, and I cannot?’”

Ketu Mala said she didn’t experience gender equality until years later, when on retreat at Pa-Auk Forest Monastery. There, thanks to a progressive abbot, women could go anywhere they liked. Now, Pa-Auk is her home, and she wears the brown robes of a forest monastic. This type of acceptance, though, feels threatening to the leading monks in Burma.

“If I am talking to the monks, I have to move wisely and carefully,” said Ketu Mala, explaining that she must bow when she speaks to the bhikkhus and sit below them. “Some of them think that if I am talking about the gender issue, I am in competition with them. So I just have to explain to them: ‘This is not to compete with you. This is just for our confidence, for women.’”

She says the monks fear the return of the bhikkhuni sangha—the order of fully-ordained women that died out in Burma and other Theravadan Buddhist countries a thousand years ago. Since then, women have not been able to receive full ordination because the Buddhist monastic code requires a nun to be ordained by both the bhikkhu and bhikkhuni sangha.

In Mahayana Buddhist countries, the bhikkhuni tradition has been revived. And in Theravadan Sri Lanka, the bhikhuni sangha is making a comeback. Still, Ketu Mala says that she can’t talk about the bhikkhuni sangha in Burma.

She is wise to be cautious: under Burma’s former military government, a woman ordained as a bhikkhuni abroad was imprisoned for her actions upon her return home.

“So in Burma it’s not easy to talk about gender,” Ketu Mala said. “[But] in Buddha’s time, when he was preaching, on one side there were the male monks and on the other side, the female monks. He gave them an equal role.”

For Ketu Mala, this kind of equality is a long way away—a feeling that hit home earlier this year when she clashed with a monk in the audience of one of her religious lectures. The monk had stated that he did not believe the Buddhist concept of metta, or lovingkindness, ought to be extended to everyone regardless of merit. Ketu Mala disagreed. “This is wrong,” she said fiercely. “As a Buddhist monk, he should not say this. Buddha would never talk like this—he says you must have compassion for all people.”

But the clash likely had causes that ran deeper than the simple disagreement. “I think he was not happy that for the first time, there is a nun on the stage and he is down in the audience. Burma is a male-dominated country, and the monks are always in a higher place.” The incident drew the attention of Burmese newspapers and social media.

In Burma, nuns are called thilashin, the owners or protectors of virtue or ethics. Ketu Mala’s passionate response in the face of the monk’s challenge suggests that it is a fitting title. But despite this honorific, nuns are still not taken seriously.

“Even though they are called thilashin, they do not have a good reputation in society. Many think girls become nuns because they have a problem—no money or no family,” Ketu Mala said.

Changing opinions like this will be an uphill battle, but it is one that Ketu Mala is committed to fighting.

“People in Burma are more interested in women’s rights now. But the nuns are also women: they are struggling, they are discriminated against in the religious sector. I think society has forgotten the nuns. So I would like our women to remember them,” she said.

“We have to show that we are standing up for ourselves,” Ketu Mala said. “ If society accepts that we can [stand up for ourselves], we can do most things.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Ketu Mala as a bhikkhuni. She is a thilashin. —The Editors

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.