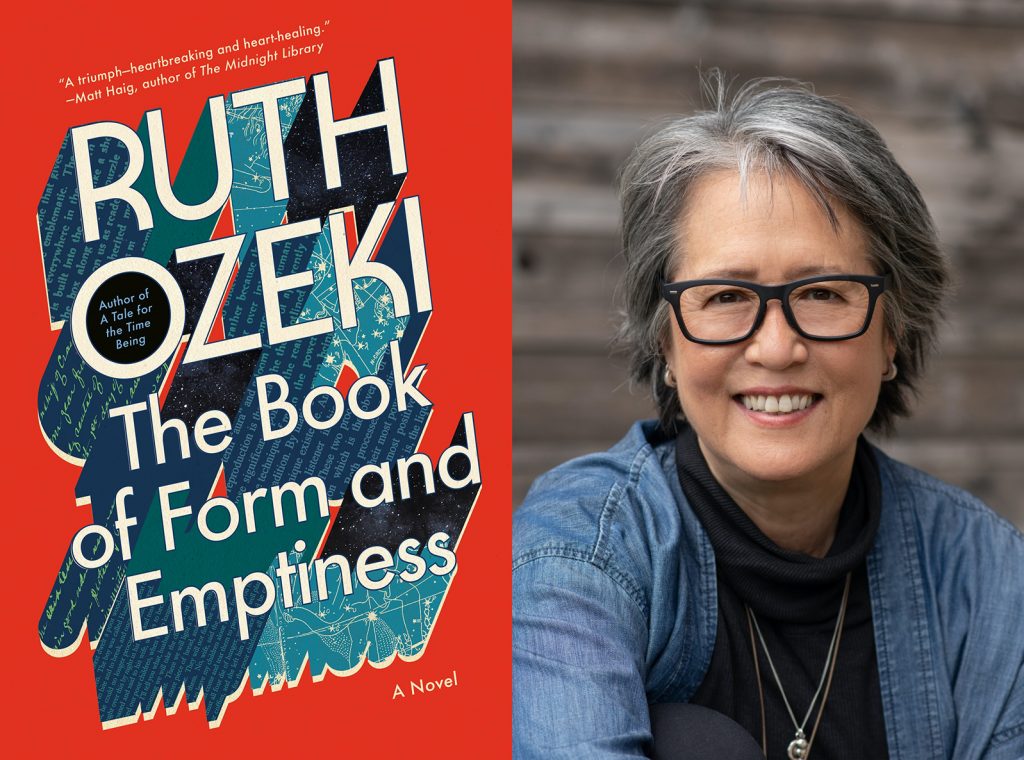

On a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief James Shaheen spoke with Ruth Ozeki, a novelist, filmmaker, and Zen Buddhist priest, to discuss her new novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness. The book follows the story of a young boy, Benny Oh, who begins to hear the voices of everyday objects after his father’s death. In this poignant exploration of grief, creativity, and madness, Ozeki weaves together Zen Buddhism, global pop culture, environmental politics, and the writings of German philosopher Walter Benjamin—not to mention a whole cacophony of voices.

During their conversation, Ozeki and Shaheen tease out some of the Buddhist strands within the novel, including a central teaching of the Heart Sutra, Dogen’s fascicle on insentient beings speaking the dharma, and a particularly evocative story of Kannon, the bodhisattva of compassion. Ozeki also shares how the process of writing helps her find redemption and resolution through relationship. Learn more about The Book of Form and Emptiness and Ozeki’s contemplative approach to writing in the interview excerpts below, and listen to the full episode here.

***

On her new novel

The Book of Form and Emptiness tells the story of a twelve-year-old boy named Benny Oh whose father dies in a tragic and stupid accident. Benny is left with his mom to grieve, and he starts to hear his father’s voice calling his name. This is something that is not uncommon: when a loved one passes, very often people will hear their voice. This happened to me after my dad died. For about a year after his death, I’d be washing the dishes or folding the laundry, and suddenly from behind me, somewhere, I would hear him calling my name. I’d whip around to see, and of course, he wouldn’t be there because he was dead. At that moment, I’d experience an upwelling of grief and loss. This happened several times, but then eventually it tapered off and faded away, and I forgot about it.

With Benny, on the other hand, it doesn’t taper off and fade. In fact, he becomes even more receptive to the voices and the feeling tone of things in his environment. He starts to hear the voice of a sneaker calling to him or a Christmas ornament or a piece of wilted lettuce. This constant cacophony of voices causes Benny to suffer, until he eventually finds refuge at a large public library. Libraries are filled with talking objects, but books know how to speak in their library voices. They know how to whisper.

Soon, Benny starts meeting these wonderful denizens of the library: a philosopher-poet named Slavoj; a young performance artist he falls in love with; and librarians with magical powers because, of course, all librarians have magical powers. But the most important relationship he makes there is with a very special book. It’s his book. The book speaks to him, as books do, and begins to narrate his life. In doing so, the book helps Benny find a way not only to be with all the voices but also to find his own.

On form and emptiness

The book takes its title from a key teaching of the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form.” It’s referring to the notion of dependent co-arising, or what Thich Nhat Hanh calls interbeing. I’ve always thought about interbeing in terms of the relationship between a wave and the ocean: A wave pops up and gets bigger and bigger and bigger, and it looks around and thinks, “Whoa, look at me. I’m a wave. I’m really something.” The wave is just sitting there enjoying its selfhood, and then suddenly it realizes that it’s becoming less and less. The wave starts freaking out, cries out for help, and then merges back into the ocean.

Of course, everything in the world is like that. We have this brief moment of thinking, “Oh, look at me, I’m something,” and then boom, it’s over. There’s something so beautiful about this idea of things coming into being and then falling back into a great ocean of interconnectivity. That’s really what the creative process feels like to me: there’s a generative impulse that allows a book or a poem or any work of art to come into being temporarily and then return.

On finding redemption through writing

For me, the process of writing is redemptive. Yes, we have suffering. Yes, we have questions, confusion, and delusion. But writing is the work that I do to find a way of being with these experiences. What’s really wonderful about writing fiction in particular is that you get a chance to rewrite. In writing a novel, I can take the questions of life that perplex or confuse me and then test them. It’s like a thought experiment: I write and then rewrite and rewrite until some kind of resolution emerges.

That’s why we read too. We think of the writer as being the person who writes the book and the book as an object, solid and unchanging. But the book is a mutable object. I can write a book and you can read it, and in doing that, we’ve engaged in a process of cocreation. The book that you read is not the book that I wrote. You’re bringing your entire lived experience to it. That holds true for every reader in the world who reads this book, so if the book sells half a million copies, then that’s half a million different books out there in the world. They propagate. I can write something, but I have no idea and no control over how the book is read and what it becomes in the hands of another reader. And that’s exciting to me.

On teaching embodied writing

The best writing is embodied writing. When you read writing that’s clichéd, for example, you can tell that the writer has not taken the time to drop back into their body and feel what the character is experiencing. We have so many devices and ways of sucking ourselves out of our bodies into cyberspace, and it’s hard to write from that disembodied place.

When I teach creative writing courses, I teach my students how to drop back into the body, as well as how to be patient. Writers are impatient. I’m impatient. Most writers I know don’t want to write—they want to have written. This is something that we all struggle with, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing. We just need to learn how to sit with our impatience because somewhere in that tension between patience and impatience, there’s a generative impulse that can emerge.

This is something that meditation can teach you. It’s a very helpful practice not just for writers but for all human beings. Even if my students forget everything else I’ve taught them, maybe they’ll remember the experience of sitting quietly and being intimate with their mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.