The ordination debate is not new, and it’s not going away. While some believe that efforts to reinstate full bhikkhuni ordination for women monastics into the Theravada tradition represents a departure from the vinaya—a monastic code of conduct attributed to the Buddha—others argue that its return marks the actualization in the present day of the fourfold assembly, the four-part sangha of ordained men, ordained women, lay women, and lay men.

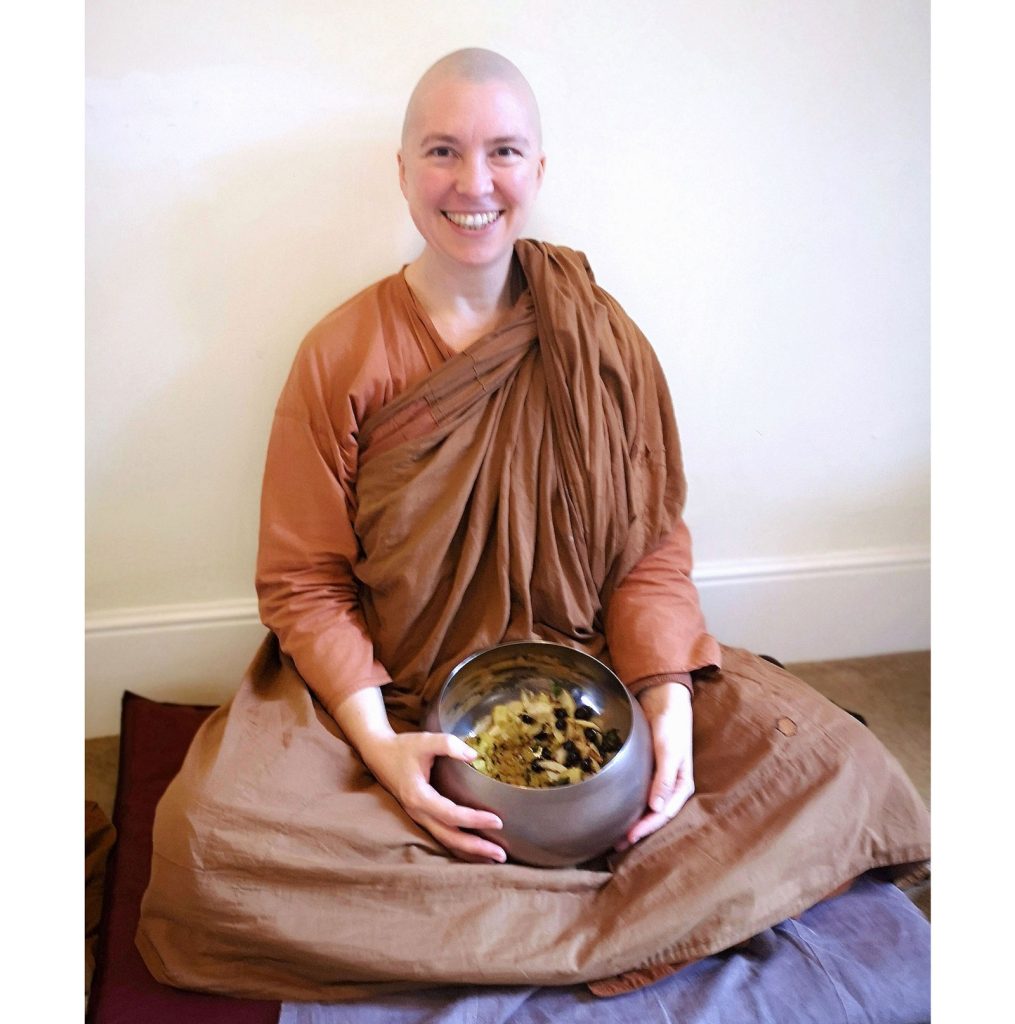

Some monastics are now trying to realize this assembly in their own backyard. Ven. Canda is an ordained bhikkhuni who has practiced in the vipassana tradition as taught by S.N. Goenka and in the Thai Forest tradition with Ajahn Brahmavamso Mahathera, better known as Ajahn Brahm. After studying in Burma for several years with Sayadaw U Pannyajota, Ven. Canda joined Dhammasara monastery in Perth, Australia, undergoing full bhikkhuni ordination in April 2014, with Theravada nun Ayya Santini as preceptor. She’s also head of the Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project, an organization working to establish a monastery for bhikkhunis in the UK.

Ven. Canda has been a nun for over ten years, but it wasn’t until she left her monastery in Burma that she realized how important full ordination is for the well being of women monastics. She recently spoke with Tricycle about the questions and biases that continue to surround ordination and how to work toward equality without burning out.

***

Why is it so important for bhikkhunis to have their own space to live and practice? I actually think the most important thing is the ordination in itself, even over and above having space. Until women are given equity in terms of their ordination platform, they won’t receive the same support as monks. Right now, many nuns don’t have the independence to live separately from monks because they depend on monks to provide food and the environment for practice.

Only bhikkhunis have the ability to ordain other nuns, so if you’re not fully ordained, you don’t have a lot of autonomy in developing or building a community. It’s also very important for laypeople to see Buddhism give equality to women. People want to feel proud of their religion, rather than see it as so far behind the times. The Buddha, by ordaining bhikkhunis, was far ahead of his times in this regard!

How is full ordination different from being semi-ordained, which is the case for most nuns in historically Buddhist places like Sri Lanka and Thailand? Full ordination makes someone a recognized member of the monastic sangha. On a practical level, fully ordained nuns have more disciplinary rules, which are very helpful in establishing strong mindfulness and deepening meditation practice. As I said, with ordination also comes more autonomy to create our own sanghas and make decisions. But it takes time to establish this kind of equity and to educate the public about the issues we face. At the moment [in Theravada communities], there is a strong cultural bias toward supporting monks, rather than nuns. Being told, as a woman, that you have a kind of second-class ordination has psychological effects. It’s like being told you’re not quite as good, that you’ve got to prove yourself more, or try harder.

When I first became a nun, however, I didn’t realize the importance of ordination. When I started living and studying in Burma with my teacher Sayadaw U Pannyajota, he basically told me that there was no bhikkhuni ordination available, but that I would be living as a nun. For me, that was enough––it was an ordination from the heart, a huge renunciation that for years I had prepared for. I didn’t see any need for technicalities or fine print about the number of precepts. None of it would have made a huge impact on my actual practice life then, anyway, because the right conditions were in place. It was only later, when I got very sick and had to leave the monastery, that I realized how important full ordination is.

As a monastic, you’re very dependent on your base monastery. If you stay there you’ll be supported, but once you move away, sources of support and places to stay are few and far between. And as a nun, you’re not recognized by laypeople as worthy of support in the same way that monks are––as the optimal “fields of merit”––so things are even more difficult.

But even with full ordination, nuns are subject to extra rules that the monks don’t face. How do we work with these biases that seem to be built into the tradition itself? It’s a matter of understanding where the rules come from—why they were formed and how to apply them in a practical and compassionate way. Pali scholars can help tell us which rules were most likely laid down by the Buddha, which were introduced later, and which have been, perhaps, exaggerated in order to restrict women’s ordination further.

I do not suggest that the rules should be altered in any way, and I don’t consider [bhikkhuni ordination] a changing of the rules according to our time. The way I’m observing the vinaya does not have anything to do with me being a modern woman, as some might allege. The vinaya always has been—and must be—a living, adaptive system; the point is that we’re trying to understand this ethical rulebook in a skillful, compassionate way. In fact, the vinaya began as a series of responses that the Buddha said when certain quandaries happened in the sangha. It’s not a system of law, it’s more like the Buddha was asking us to think about the consequences of our actions and gently nudging the monks and nuns in the right direction. It’s our job to use our wisdom to try to understand what he meant, and how to apply these rules in any given situation.

What is your response to people who say that the current system of full Theravada bhikkhuni ordination—which is a result of collaboration with Mahayana nuns—is inauthentic? That’s an old argument at this stage. I think that if you want to find fault with bhikkhuni ordination, you can—and you will—find fault with it. There are only very artificial differences between the Mahayana and Theravada vinaya, so in my opinion, bhikkhuni ordination is authentic.

How and why did you decide to found the Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project? In October 2015, Ajahn Brahm asked me to take steps toward establishing a monastery in the UK to increase equality in practice and ordination opportunities for women, and thus the Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project was born.

The Buddha said [in the Digha Nikaya] that he wouldn’t pass on until the fourfold assembly of bhikkhus, bhikkhunis, laywomen, and laymen was fully established. A goal for the Anukampa Bhikkhuni project is to realize this assembly.

I’d already been a nun for about ten years. I realized there was a scarcity of actual conducive conditions for women to ordain into, and very few opportunities for us to take full ordination. It was really a matter of figuring things out step by step on the ground. So it was very grassroots.

I’m English; I was born and brought up here, but left when I was 18. Until I came back, I lived most of my life in Asia and Australia. Coming back was almost like visiting a new country—I also found myself getting to know my own country from the perspective of a nun. I didn’t really know anybody here in the UK who could offer a place to stay. That support network formed over time.

What advice do you have for people who are working against injustice who want to practice acceptance and also work toward amending the problems they see? We need to learn to have a wholesome relationship to all of our experiences, whether we are unequivocally averse to them or not. Ajahn Brahm talks about “kindfulness,” which I think goes straight to the heart of the Buddha’s teachings. We need to combine our awareness of what is with kindness and right intention. This kind of attitude should be at the forefront of our minds and inform our relationships to any experience that we have.

In terms of activism, if we’re coming from a place of frustration and despair, we are less effective and more prone to burnout. I see meditation as a way to learn how to handle our emotions in a skillful way. When we work from a place of awareness and kindness, we’re able to better understand where to put our energy, when to take breaks, and how to act wisely when confronted with a trying situation.

♦

Further reading: To learn more about the challenges that women monastics face in the Buddhist world today, read this interview with nuns Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta and our guide to bhikkhuni ordination.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.