Three-year retreat is one of the focal points of committed Tibetan Buddhist practice. And yet there are virtually no published, first-person accounts of what it entails to spend three years, three months, and three days in intense, sometimes solitary, practice. Vicki Mackenzie’s Cave in the Snow, a third-person narrative of Tenzin Palmo’s twelve years in a mountain cave, revealed little of that practitioner’s personal, inner journey. Diane Rigdzin Berger’s memoir exposes a great deal.

Most three-year retreats occur in a group setting, and the rules of such a retreat, specified by the supervising lama, usually restrict broadcasting details about specific practices and inner experiences to outsiders. In Berger’s case, the rules were a little more relaxed, and although she couldn’t give details of specific practices, her story comprises a rich tapestry from which anyone knowledgeable about Tibetan Buddhism can get a clear picture of what she was practicing and how these practices affected her. We can also be thankful that the author is an experienced writer with a gift for description and a poetic touch. She brings the reader right into the heart of her retreat.

Not only was this a solo retreat, but necessity required Berger to move from place to place, supported by friends, family, and sangha members in several Pacific Northwest locales. Her retreat was directed by Kilung Rinpoche, lama and head of the Pema Kilaya sangha, based near Seattle. Berger draws on journal entries from the retreat and reflections added once she had decided to write a book about it.

The texture of Berger’s memoir is flowing and atmospheric. Closed retreat brings greatly heightened sensitivity, and here she is generously open, giving the reader access to everything from her emotional struggles and occasional physical difficulties to her insights, dreams, and inner reactions to practice. All of this is richly embroidered with references to the abundant wildlife that inhabited her various retreat settings and her feelings of close attunement to the natural world.

Despite the unusual mobile aspect of the retreat, we are given a very clear idea of what it means to be in a long, solitary, and essentially traditional Tibetan Buddhist retreat. Berger often practiced five or six sessions per day. Appropriate altars were maintained in each setting. Full attention was given to protectors and local spirits. Sang and incense offerings (such as the well-known Riwo Sangchö) were performed regularly. Her practices included Dzogchen meditation, deity sadhana practices, lengthy mantra recitation, foundational practices (ngondro) and prostrations, predawn fire pujas, daily tsoks (food offerings), and other rituals. Anyone familiar with the more advanced Tibetan Buddhist practices can guess what other, more esoteric, activities Berger was engaged in.

But why would a Westerner, and in particular Diane Berger, attempt such a feat? “To achieve enlightenment?” or “to be free?” This is, of course, the final goal for all Buddhists. But deep practices—especially those addressed in long retreats in this tradition—are done more specifically to remove obstacles to realization. And what that boiled down to for Ms. Berger, as she explains it, was to free herself from the distractions and sidetracks she had acquired from life. Perhaps these could be called her personal neuroses. Berger came to her retreat as a seasoned meditator, with decades of experience in the Tibetan tradition. She had received teachings from a number of highly regarded lamas and had practiced in Tibet and Nepal. But she was not, by nature, a recluse. Leading an exceptionally active life, early on she had worked as a journalist and later helped found a humanitarian foundation and a Buddhist sangha. Like many modern people, she was engaged with society and proactive. She had married twice, raised children, and had grandchildren.

Contemplating in her journal the benefits of her retreat, she wrote, “And now, somehow, perhaps that is the big miracle after these three years—it has become simple to sit for practice. No underlying diversionary pull, no addictive ideas, no some-thing else.”

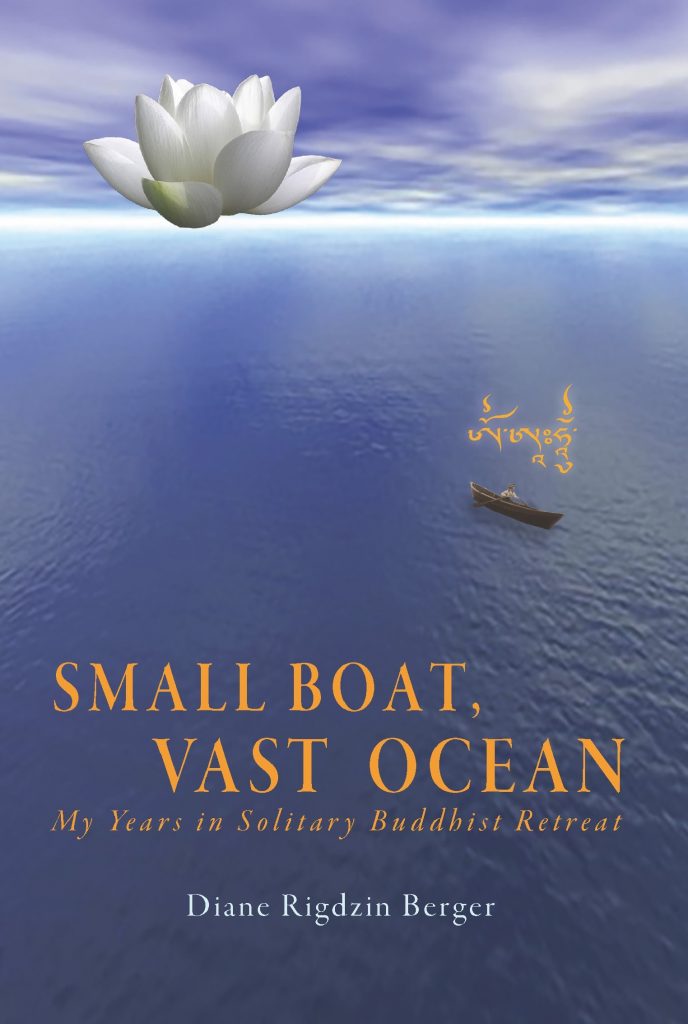

Because her book is so open and honest about her inner world and its difficulties—similar to those all of us in the modern world acquire—we are given a realistic picture of what deep Tibetan Buddhist practice can release us from and how that comes about. This became especially clear in those transitional moments when Berger moved from one venue to the next—by car, ferryboat, and even a small airplane. Anyone who has done long solo retreat knows how overwhelming it can be to suddenly need to engage other people, to encounter the normal chaos of a supermarket, to set up a new living space. At these moments, our ingrained mental and emotional patterns suddenly reveal themselves. Such encounters are woven into the multicolored fabric of Small Boat, Vast Ocean.

At the same time, it also becomes clear that the guidance of an experienced mentor was essential. (For an uninitiated person to “cook book” such a journey from written material would be impossible and potentially dangerous.) The retreat was designed for her specifically by Kilung Rinpoche, and Berger consulted with him frequently, either via in-person visits or by phone. In some of those moments when the ground seemed to fall out from under her feet, her teacher’s advice and support kept her on track.

By literally making her three-year retreat an open book, Berger has given those on the spiritual path an incredible gift. Readers who wish to deepen their knowledge about Tibetan Buddhism, or those considering long solo retreat, will find Small Boat, Vast Ocean entertaining and enlightening.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.