Written after the passing of her father, Phantom Pain Wings is a remarkable achievement from one of South Korea’s most heavily revered and imaginative poets, Kim Hyesoon. While the poems of this collection center on grief and death, they never aim for consolation or an easily digestible sentiment but rather create parallel worlds, separate from reality and simultaneously separate from the memories or images that conjured them into being. In “Korean Zen,” the writer explores grief through a reckoning with her country’s Buddhist traditions as well as the limits of language and poetry itself. In the book’s penultimate piece, “Bird Rider: An Essay,” Kim lays out what can be seen as the thesis of the collection, noting the inability of the medium to comfort or console the reader, as the poet can produce only “failure, grief, and self-erasure.” Kim writes: “Just as there is no geometric or genetic consolation, literary work merely constructs an afterimage or alternative symmetrical pattern of the event that occurs.”

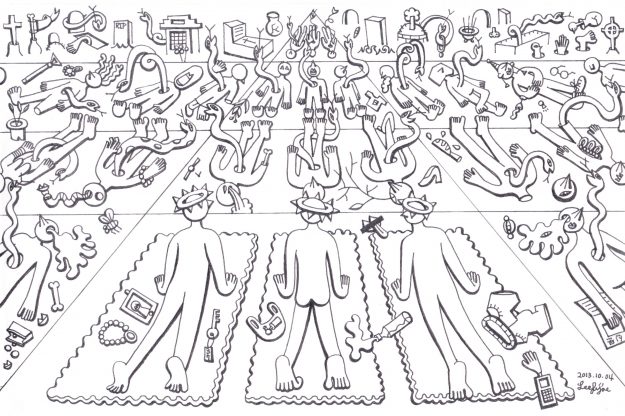

In many ways, this idea of the false reality or afterimage contains echoes of the Buddhist concept of sankhara. Kim’s work is full of paradox, a poetry that disavows Buddhism and yet simultaneously creates and lives within imagined Buddhist worlds. In an interview that appeared in conjunction with the Poetry Parnassus festival in London in 2012, Kim asserts that she was actually raised in a more Christian environment, and yet her poetry is filled with Buddhist references—to samsara, to asuras, to bodhisattvas, and, as is exemplified in the featured poem, Zen. In the same interview, Kim states: “I think Buddhism is more than a religion, it is first a process of discipline, and Buddha is one who has gained wisdom rather than being a god.” Much like the real is never achieved, Buddhism is never explicitly revoked. Rather than give you what you came for—catharsis—Kim is more inclined to let you linger in the pain, in the worlds she creates; alternate realities where the questions that arise open up to multitudes, koan-like in their wisdom, more valuable than the relief they refuse to confer.

Korean Zen

Even if I don’t blink

my eyelashes write on my face

(but I don’t have any eyelashes)

I tolerate time

as I lift up strands of hair from the crown of my head

to write on empty space

(but my head’s shaved)

For how long can humans endure silence?

But I’m listening to the typewriter

of the girl above my pelvis who is typing

(For how long can humans stay inside a poem?)

Bird floats me high up then

takes off alone

I can’t tolerate the sky

like the way I can’t tolerate poetry

I think of a plump girl called Ego

Tonight I need to starve her to death

Maybe I’m killing the future before the past

by killing the girl in order to attain nirvana

But who’s breaking the swishing

windshield wipers of my heart?

I pick up the receiver of a red phone

that’s been ringing nonstop

inside a pocket made of bone

It’s that girl

♦

“Korean Zen,” by Kim Hyesoon, translated by Don Mee Choi, from Phantom Pain Wings, copyright © 2019 by Kim Hyesoon. Translation copyright © 2023 by Don Mee Choi. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.