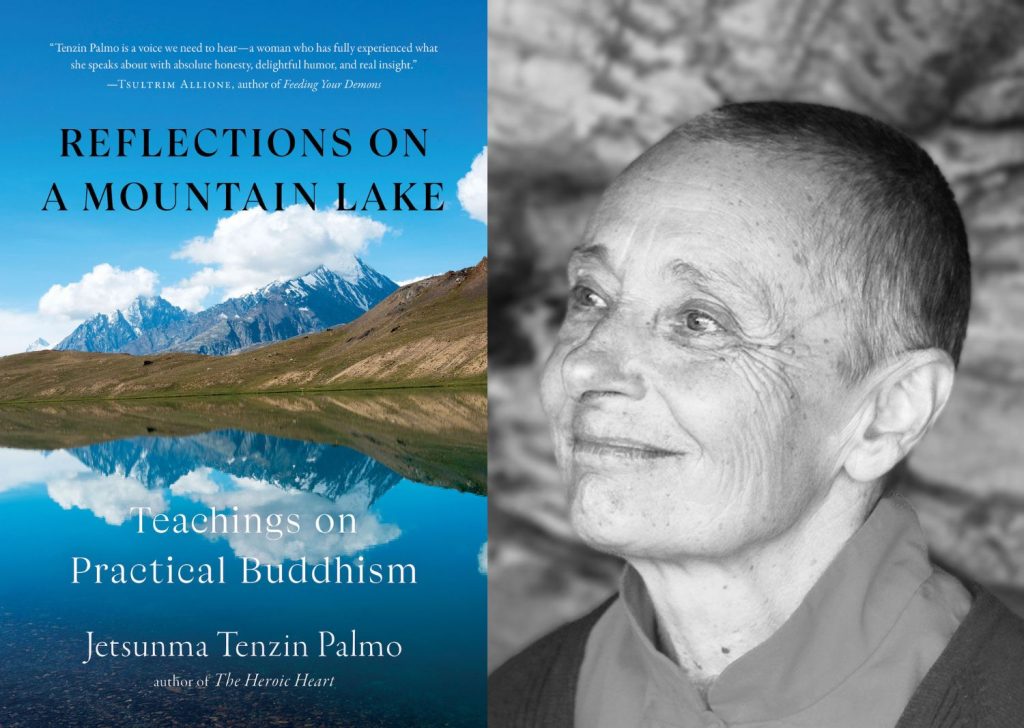

In an excerpt from Reflections on a Mountain Lake: Teachings on Practical Buddhism, a classic collection of dharma teachings re-released this month, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo reflects on the wisdom of non-knowing and how she’s dealt with her own questioning over the years.

In certain religions, unquestioning faith is considered a desirable quality. But in the buddhadharma, this is not necessarily so. The Buddha described the dharma as ehi passiko, which means “come and see,” or “come and investigate,” not “come and believe.” An open, questioning mind is not regarded as a drawback to followers of the buddhadharma.

A mind which says, “This is not part of my mental framework, therefore I don’t believe it,” is a closed mind, and such an attitude is a great disadvantage for those who aspire to follow any spiritual path. But an open mind, which questions and doesn’t accept things simply because they are said, is no problem at all.

There is a famous sutra which tells of a group of villagers who came to visit the Buddha. They said to him, “Many teachers come through here. Each has his own doctrine. Each claims that his particular philosophy and practice is the truth, but they all contradict each other. Now we’re totally confused. What do we do?” Doesn’t this story sound modern? Yet this was 2,500 years ago. Same problems. The Buddha replied, “You have a right to be confused. This is a confusing situation. Do not take anything on trust merely because it has passed down through tradition, or because your teachers say it, or because your elders have taught you, or because it’s written in some famous scripture. When you have seen it and experienced it for yourself to be right and true, then you can accept it.”

Now that was quite a revolutionary statement, because the Buddha was certainly saying that about his own doctrine too. In fact, all through the ages it has been understood that the doctrine is there to be investigated and experienced, “each man for himself.” So one should not be afraid to doubt. Stephen Batchelor wrote a dharma book entitled The Faith to Doubt. It is right for us to question. But we need to question with an open heart and an open mind, not with the idea that everything that fits our preconceived notions is right, and anything which does not is automatically wrong. The latter attitude is like the bed of Procrustes.

You have a set pattern in place and everything you come across must either be stretched out or cut down to fit it. This just distorts everything and prevents learning. If we come across certain things that we find difficult to accept even after careful investigation, that doesn’t mean the whole dharma has to be thrown overboard.

Even now, after all these years, I still find certain things in the Tibetan dharma which I’m not sure about at all. I used to go to my lama and ask him about some of these things, and he would say, “That’s fine. Obviously you don’t really have a connection with that particular doctrine. It doesn’t matter. Just put it aside. Don’t say, ‘No, it’s not true.’ Just say, ‘At this point, my mind does not embrace this.’ Maybe later you’ll appreciate it, or maybe you won’t. It’s not important.”

Our minds do become more open and increasingly vast as we progress. We do begin to see things more clearly, and as a result they slowly begin to fit into place.

When we come across a concept which we find difficult to accept, the first thing we should do, especially if it’s something which is integral to the dharma, is to look into it with an unprejudiced mind. We should read everything we can on the subject, not just from the point of view of buddhadharma, but if there are other approaches to it, we need to read about them, too. We need to ask ourselves how it connects with other parts of the doctrine. We have to bring our intelligence into this. At the same time, we should realize that at the moment, our level of intelligence is quite mundane. We do not yet have an all-encompassing mind. We have a very limited view. So there are definitely going to be things which our ordinary mundane consciousness cannot experience directly. But that does not mean these things do not exist. Here again, it is important to keep an open mind. If other people with deeper experiences and vaster minds say they have experienced it, then we should at least be able to say, “Perhaps it might be so.” We should not take our limited, ignorant minds as the norm. But we must remember that these limited, ignorant minds of ours can be transformed. That’s what the path is all about. Our minds do become more open and increasingly vast as we progress. We do begin to see things more clearly, and as a result they slowly begin to fit into place. We need to be patient. We should not expect to understand the profound expositions of an enlightened mind in our first encounter with them. I’m sure we all know certain books of wisdom that we can read and reread over the years, and each time it seems like we are reading them for the first time. This is because as our minds open up, we begin to discover deeper and deeper layers of meaning we couldn’t see the time before. It’s like that with a true spiritual path. It has layer upon layer upon layer of meaning, and we can only understand those concepts which are accessible to our present level of mind.

I think people have different sticking points. I know that things some people find very difficult to grasp were extremely simple for me. I already believed many of the teachings before I came to the buddhadharma. On the other hand, some things which were difficult for me, others find simple to understand and accept. We are all coming from different backgrounds, and so we each have our own special problems. But the important thing is to realize that this is no big deal. It doesn’t matter. Our doubting and questioning spur us on and keep us intellectually alert.

We can be quite happy with a question mark.

There have been times when my whole spiritual life was one great big question mark. But instead of suppressing the questions, I brought up the things I questioned and examined them one by one. When I came out the other end, I realized that it simply didn’t matter. We can be quite happy with a question mark. It’s not a problem at all actually, as long as we don’t solidify it or base our whole life on feeling threatened by it. We need to develop confidence in our innate qualities and believe that these can be brought to fruition. We all have buddhanature. We have all the qualities needed for the path. If we don’t believe this, it will be very difficult for us to embark because we have no foundation from which to go forth. It’s really very simple. The buddhadharma is not based on dogma.

♦

From Reflections on a Mountain Lake: Teachings on Practical Buddhism by Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo © 2002 by Tenzin Palmo. This edition published 2023. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.