THE LATE KARMAPA loved birds. Westerners called the regal guru “the St. Francis of Tibet,” for he was often seen at his monastery in Bhutan with birds perched on his shoulders or eating from his hand. Song birds and birds of silence, those of brilliant plumage and dull-breasted females, carnivores and seed eaters—all were welcome in his court.

Once I heard about a time during the mid-seventies when the Karmapa and his retinue were staying with some young American friends at the splendid Oberoi hotel in New Delhi. Inspired by Baba Ram Dass, Leo Heistein had quit his medical practice in California and he and and his wife Susan had come to India to study with a secluded mountain yogi. But having met the Karmapa several years earlier and recognized the supremacy of his wisdom mind, they had courted his friendship and eagerly responded to his suggestion that they join him on his visit to Delhi. In his presence, they maintained the strict vegetarian diet of their Vedanta tradition, and would sometimes engage His Holiness in friendly debates about the different views of “self” expressed in the Brahmanic and Buddhist traditions.

One afternoon during their stay in Delhi, the Karmapa suggested that they visit the Jain hospital for birds in the old section of the city. A black Mercedes with a mango-turbaned chauffeur transported them through the dense maze of the Lajpat-Rai, the market that nestled into the shadows of the ancient Red Fort. The smell of dust filled the air and smoke-twists rose from the dung fires that heated vats of oil-drenched take-away foods, which were handed to customers wrapped in sheets of newsprint. The driver yelled and waved his arms at the throngs of people, sacred cows, and laden ox carts that jammed the narrow streets. From inside the Mercedes, they saw men walking naked, carrying nothing, their gaunt dusty bodies drawing no attention, while women, holding deformed and blind babies up to the windows, moaned “baksheesh, baksheesh.” Everywhere puddles of yellow shit, and betel leaf spittle coughed up like blood, were ground into the dirt streets by fast-moving bare feet.

At the entrance to the red brick hospital they were greeted by attendants swathed in white cotton and who, in keeping with the Jains’ indiscriminate reverence for life, wore white gauze masks over their mouths to prevent the unwitting entrapment of invisible organisms.

They had barely passed the entryway when uncaged birds began to gather around the Karmapa. Some had little splints like toothpicks to help heal broken bones, others hobbled with a lame leg, and one female peacock had no legs at all. The Jains were very polite to the Tibetan holy man and gladly escorted him and his friends through the hospital.

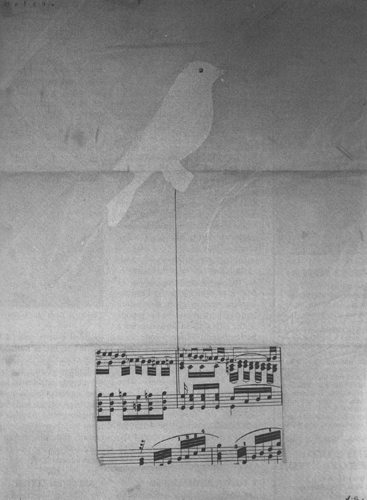

As they inspected rows of crowded wire cages, His Holiness discoursed on the karmic order of birds. Songbirds came first. Pleasing to both the eyes and ears, these creatures were also virtuous in their feeding habits, eating only seeds, and through their droppings sowing flowers and fruit trees. Indeed, their habits, their diminutive beauty, and the tranquility induced by their music merited their unequivocal place in the order of birds. But the bottom of the order offered no such clarity. Who should be the very last, wondered the Karmapa-birds of prey, or those scavengers that fed off carrion? Turkey vultures, for example, did not themselves kill, but offered none of the majestic grace of a hungry hawk nor the stunning aptitude of a trained falcon.

The Karmapa had laughed at this dilemma, and laughed too because he was happy to see so many birds diligently cared for by the kind Jains. It had been a fine afternoon, and upon driving back His Holiness invited his American friends to dinner in the hotel’s plush dining room.

A few hours later, after bathing and changing into fresh Indian clothing, Leo and Susan joined the Karmapa and his monks. Waiters in starched white cotton stood stiffly at attention near a rectangular banquet table that had been laid with a pink linen cloth, crystal glasses, gold-rimmed plates, and polished cutlery. The Karmapa had already taken the liberty of ordering a five-course feast.

This was not the India to which the American seekers had grown accustomed, but they welcomed this luxurious respite from their humble mountain retreat. And bolstered by the gracious setting and their convivial host, their conversation quickly became animated and lighthearted. The dining room began to fill, and across the floor, from a trio in tuxedos, came the familiar strains of Viennese waltzes.

Soon, the waiters placed two silver platters on either side of the table and proceeded to efficiently serve chunks of baked chicken smothered with a marsala sauce. The Tibetans eagerly took up their forks. But Leo and Susan remained dumbfounded. The Karmapa said nothing and appeared to take no notice of the discomfort aroused in his American guests. Minutes later, two more platters arrived, this time with whole tiny roasted pheasants laid to rest on a bed of colored rice, their little eyes smaller than the fresh red tikkabetween Susan’s brows. Leo could contain himself no longer. Making a sweeping gesture over the platters, he glared at the Karmapa and sputtered, “I just don’t get it.”

Undisturbed, the Karmapa continued eating, then smiled gently, shrugged, and quietly said, “It’s a paradox.”

Leo sighed and hung his head. After a few minutes he picked up his fork. Susan joined him and the young couple thoroughly enjoyed the rest of the feast, which consisted of a third course of curried chicken, followed by two platters of tandoori squab and a final offering of fresh fruits arranged with a variety of colorful sorbets.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.