What does it mean to live an ethical life? And how can cultivating wisdom and virtue support us in navigating the crises of today’s world?

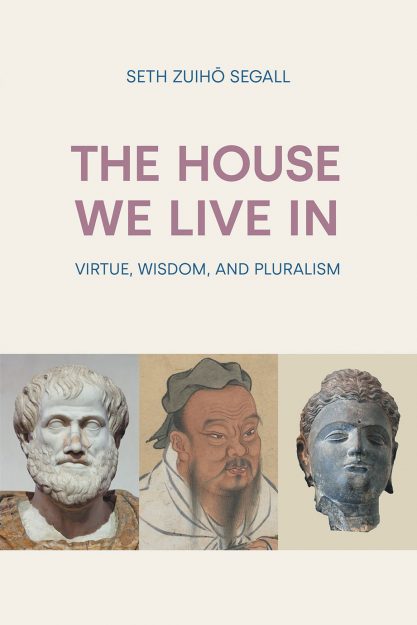

These questions are at the center of Zen priest and psychologist Seth Zuiho Segall’s new book, The House We Live In: Virtue, Wisdom, and Pluralism. Drawing from Aristotelian, Confucian, and Buddhist ethical traditions, Segall outlines a vision of liberal pluralism grounded in human flourishing.

In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sat down with Segall to discuss how he understands the relationship between enlightenment and human flourishing, what we can learn from comparing different understandings of virtue, and how cultivating philosophical wisdom can impact our everyday lives. Read an excerpt from their conversation, and then listen to the full episode.

To start, can you tell us about The House We Live In and what inspired you to write it? There are a couple things that inspired me to write it. One was just the sheer shock of the 2016 election and a concern for the well-being of democracy and civility and our ability to talk to each other across the political divide and remain human to each other. Another was a sense that we’re living in a very pluralistic society with people from different ethnicities and different sectarian beliefs. We live in a country of Buddhists and Hindus and Sikhs and Christians and Jews and Muslims and atheists and agnostics and the spiritual but not religious and so forth. Somehow we all have to get along together. And even though we have different value systems and different beliefs, we have to have some kind of common ethics that allows us to relate and connect and cooperate with each other. I was looking for an ethical system that might aspire to be transcultural.

In my previous book, Buddhism and Human Flourishing: A Modern Western Perspective, I was trying to reach a modern version of what flourishing might be like based on a synthesis of Aristotle’s idea of eudaimonia and the Buddhist idea of enlightenment. How could we somehow bring these into connection with each other? In the last few years, I’ve also been reading a lot from the Confucian tradition, and I realized that it was a third tradition that says flourishing depends on virtue and wisdom. I was interested in comparing these systems and seeing if I could use the resources from all three to come up with a new contemporary ethics that would be useful for us in late modern culture.

You say that the book is geared toward a vision of liberal pluralism grounded in human flourishing. How do you define human flourishing? First of all, I think that flourishing may be different in different cultures and different eras. For example, honor societies or warrior societies might have different niches in which we can flourish and different possibilities for us as human beings. But looking at the kinds of cultures we live in today, what would flourishing mean for us today?

I came up with a definition that flourishing is living a life that is emotionally fulfilling, psychologically rich, meaningful, and attuned to the ethical and aesthetic possibilities that present themselves in each moment. We’re able to enjoy a sunset and a cup of tea or be creative in some kind of way artistically, but we’re also attuned to the ethical consequences of our actions. That’s the kind of life I envisioned as flourishing.

In the book, I outline seven domains in which we flourish:

- Relationships: We’re embedded in a set of relationships with people we care about and care about us in turn.

- Accomplishment: We have a life in which we’ve made some accomplishments in areas that matter to us. That doesn’t mean winning a Nobel Prize or Pulitzer Prize, but it may mean raising a child to the point of independence so they become a decent human being, or it may be being very good on a dance floor or on an athletic field or with a potter’s wheel. It’s going to be very individual what accomplishments are meaningful for us, but we want to feel like we have some accomplishments in our life.

- Aesthetics: We’re tuned in to the aesthetic qualities of the world. We’re able to enjoy the beauty of nature, and we’re able to be creative in some kind of way.

- Meaning: We want our lives to be meaningful, which means that it matters to other people that we’ve been alive, that we’ve in some way made the world a little bit better place for the people around us.

- Whole-heartedness: We’re intensely present in the world in a complete way so that when we’re doing something, we put all of ourselves into it, body, mind, and spirit. We’re not standing back from life or hiding under a rock; we’re really engaged in the world in a meaningful way.

- Integration: If we have certain values that are really important for us, they should permeate our entire being. We don’t just enact them in some sphere and then not let them out in other spheres. Of course, we all know people who are well respected in the community but treat their children and spouses terribly or people who are inspiring from the pulpit but then sexually abuse their parishioners. The idea is that our values should permeate our entire life. People who achieve a high degree of value integration are the people we value as secular saints in the society.

- Acceptance: When hardship comes, we find ways to grow and continue to maintain and sustain ourselves. When we experience losses, we find new avenues to fulfill ourselves in and not be totally stymied and destroyed by them.

You suggest that we can foster human flourishing by looking to the traditions of Aristotelian, Confucian, and Buddhist ethics, which you describe as virtue ethics traditions. What do you mean by virtue ethics? The term “virtue ethics” was originally designated for Aristotle’s ethics, but it’s been applied to Buddhist ethics and Confucian ethics since then. The idea is that there’s an ideal state which we hope human beings aspire to. In Buddhism, for example, that ideal is being a bodhisattva or being an arhat. Each of the traditions has their own name for that higher level of being, and the way you get there is through some combination of virtue and wisdom.

Virtues are things that we have to cultivate, and we cultivate them over the course of a lifetime. In Buddhism, those virtues are going to be things like compassion, lovingkindness, and equanimity. They’ll be different in different systems, but what I found was that there’s a lot of commonality between all three systems in what’s considered virtuous. All three traditions look at a superior kind of well-being that’s the result of cultivating virtue and wisdom. It’s a lifelong cultivation—you can always get better at it.

“I don’t think Buddhism has the final answer to everything, or Confucius or Aristotle. They’re all partial visions of a larger whole.”

You say that the word “virtue” can sometimes be seen as stuffy or holier-than-thou, but you suggest that it is instead about skillfulness in the art of living. How have you come to this understanding of virtue? In Buddhism, we talk about things as being skillful or unskillful, kusala and akusala. Things aren’t bad because they’re sinful or because God disapproves them but because they’re not skillful ways to live—they’re destructive to our well-being and the well-being of people around us.

In the book, I list seven virtues that I think are universal virtues or at least aspire to be, things like truthfulness, courage, and benevolence. Each of these virtues leads to well-being. For example, if we are honest people, then others see us as trustworthy and are more willing to collaborate with us. If we recognize truth when we see it, we’re also more likely to understand the truth about ourselves and what makes us happy and what doesn’t make us happy, what leads to us being better human beings and what doesn’t lead to us being better human beings. We see things clearly.

Truthfulness is integral to well-being in that way, and not only is it integral to well-being, but it is part of what we mean by having a superior level of well-being. These virtues constitute the enlightened state as well as being pathways to the enlightened state. When we talk about someone being a bodhisattva, what are they like? Well, they’re compassionate, they manifest lovingkindness, they’re equanimous. Not only are virtues pathways to better well-being, but they’re actually the destination we want to end up in.

One of the virtues that appears across these ethical systems is practical wisdom. So how can philosophical wisdom impact our daily lives? I don’t think Buddhism has the final answer to everything, or Confucius or Aristotle. They’re all partial visions of a larger whole. When I look at the Zen masters throughout history, my own fantasy about them is that the enlightenment that each of them had is going to be different for each of them—that they each have their own partial view of the way everything fits together. Dogen says that when something is in light, that means the other side is in dark. Every vision we have of wholeness, integration, and emptiness is just a partial vision, and it’s always possible that someday we may have a greater opening.

Each philosopher brings a new vision to understanding life. When you read all these different visions, it enlarges your own sense of what’s possible and how you can look at the world. I think that’s what we get from reading the philosophers. You don’t read Plato and Aristotle and Spinoza and Whitehead and say, “Well, which one of them was right?” None of them were right. But they all had something unique to say about the world. Nietzsche and Aristotle might not agree on a lot of things, but they each have something valuable to say about the way the world is.

This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.