The following story was adapted from an upcoming novel by the author.

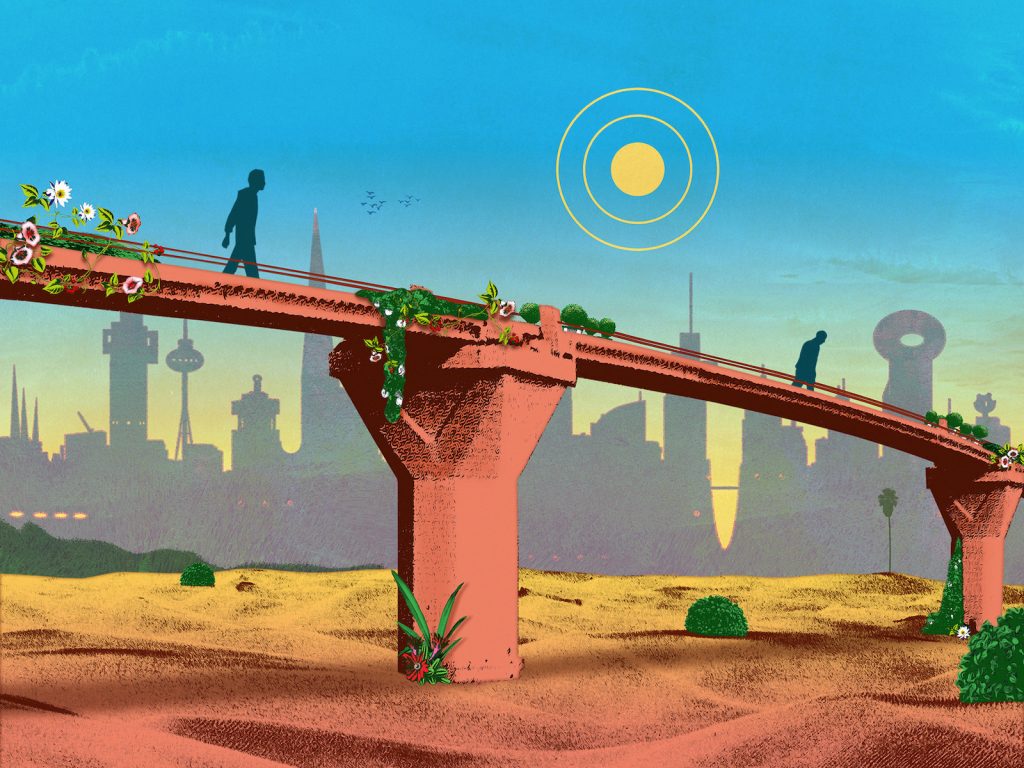

In the peculiar timespan known as the 2020s, the residents of a dying nation known as the United States—who’d been oversaturated and over traumatized with information, especially about the decay of their government, the geopolitical order, and the living Earth—elected as their leader a manic-depressive failed actor turned reality TV star. With an oversized ego, a broken heart, and no real experience or interest in governing, the first millennial President made the secret decision to devote all the powers of his office to building “the Path,” a contiguous footpath that would circle the entire planet. The goal of the Path was two-fold: to deliver unity and enlightenment to an atomized world, and to re-win the allegiance of the President’s ex.

To better know, feel connected to, and eventually manipulate his people, the President would privately turn to an anonymous social media account, which consisted of either utopian or dystopian travelogues about the new cities that were allegedly emerging beyond the President’s ability to see from his self-isolation in the nation’s capital. Wanting, naturally, to capture the source of the travelogues’ insight, the President located and kidnapped their author, an urban nomad and former Buddhist monk called the Tourist, whom the President would adopt as a secret spiritual advisor. In those brief moments between the collapse of one pillar of the American dream and the next, the Tourist would soothe the President’s existential dread by telling him stories of the so-called “New American Cities.”

This is the story of Cohenville.

Cohenville—City of Nothingness

There are enough Zen cities throughout the empire—formed in the slow chaotic years since the first masters and suzukis came to spread their gospel of nothingness—that you could walk a path from one end to the other and never miss a daily sitting.

These Zen cities take as their fundamental premise that the mind’s natural state is nothingness. And of course, there can only be one nothingness, so in this sense, it can be said that all the Zen cities are united—in some ways, even, the same city, or the same no-city. But one stands out from the others. You may have heard its name carried on the winds of gossip and reputation, or probably you’ve seen a video posted about it. I’m talking about Cohenville, that great Sparta of nothingness: an entire society devoted to the project of emptying its citizens’ minds.

Cohenville is named for one Zen’s most famous practitioners, Leonard Cohen, who’s said to have inaugurated the city when he one night sleepwalked AWOL from a West Coast monastery, experienced a possibly acid-assisted astral projection to the desert where Cohenville now sits, endured a medium-length eternity of temptations both orgiastic and suicidal, and woke up chin-deep back in the monastery’s frigid mountain stream in unprecedentedly full lotus. All of this was interpreted by one of Cohenville’s first surveyors, a Cohen fanatic, who pieced the story together from a bootleg of Cohen’s secret dream journals, a millennia-old star chart from a now-extinct tribe once indigenous to the land, and the massive mandala the surveyor found carved in the overcooked casserole of the desert floor, its fractaled petals emanating of thousand-breasted succubi and barbiturate nebulae. The surveyor went mad for 24 hours, swinging his plumb bob like David’s slingshot at anyone who approached the mandala, then woke up in satori and immediately started churning the mandala back into formless sand with his prism pole, repeating to himself with an unblinking smirk, “It means nothing. It means nothing.”

In modern Cohenville, almost all the worldly demands of being alive are taken care of on the citizen’s behalf. From automated food prep to robotic day labor, from produce selection to mate selection, the decisions and thoughts that used to be required of all humans are ceded to the greater judgment of Cohenville’s systems.

When not sitting in meditation, local Cohens inhabit the simplest of dwellings, designed according to the latest in Realm Theory precepts to be noticed as little as possible. There is minimal furniture, with walls painted black and empty of decoration. These negative aesthetics—the muting of public and private space—extend to the citizens’ bodies themselves, which are clothed only in unfitted matte khaki. The clothes were black like the walls until it was discovered that everyone looked sexier than intended, sexiness being a huge obstacle on the path to mind-emptiness.

But clothes have not been the only obstacle. If the passage of Cohenville’s generations have taught us anything, it’s how much the human injects decoration, individuation, and mind into even the smallest mandates and minutiae of being alive. In an effort to weed out all possible thought-triggers, the Authorities have established standards and laws in the fields of bathing, transportation, relationships, work, speech, and food, all designed to discourage decision, consideration, competition, artifice, invention, desire, and ego-investment of any kind in the world or the self, the loin-stirrer of the storytelling machine.

It’s said many Cohens go entire lifetimes without seeing real color, even in the eyes of other humans, the pupils of which are lasered black, a technique adapted from the empire’s prison population (which has long been an underrecognized font of innovation in the areas of meditation, liberation, and transcendence).

Children are not assigned names. Nor is there any social capital winnable by charm: every joke, affectation, and flamboyance disappears into an ether of silence. There’s no cuisine, no literature, no mathematics, no history, no community, no idea of self, no humor, and little acknowledgment of suffering, though there is inevitably some birth and death. There’s no being in love, but there is rumored to be something like dreaming—vague senses of dark endless oceans under a black sky, beneath which some report hearing a faint, pulsing sonar that pokes at a kind of primordial bottom-self, which all the city’s engineering has been unable to eradicate.

Cohenville has been in the news lately because its government—which, because Cohenville has no politics, is really just an AI-imbued mayor-computer called cohen.cohen—has recently enacted stricter enforcement of the city’s perfectly circular border, though the citizens are generally unaware of this development. But how and why is it that they don’t know? Especially in this moment, when public interest in the old Zen masters, not to mention tourism to the cities grown from these masters’ footprints, has never been higher?

You’ve answered your own question, you see. The intrusion of tourists has thrown off the entire emptiness equilibrium that Cohenville has worked so hard to cultivate. The tourists come thinking themselves pilgrims. They wear their most neutral garments, it’s true—but even the mutest tones are blindingly fluorescent to the native Cohen. It’s not just that the visitors disturb the Cohens’ Zen practice, but that in doing so the tourists force the Cohens to think. And like demons kicked up in the dust, these thoughts condense the Cohens into moments of self. And these selves—brought into the world in moments of annoyance and soon hatred—come filled with the full weight of the fall from the blissful unity of nothingness into the degradation of thinking. The disturbed Cohens have been known to inflict extremely creative atrocities on the invading tourists themselves, betraying no guilt at all, nor even disgust at the gore, as they’ve been heard to utter: this too is zazen.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.