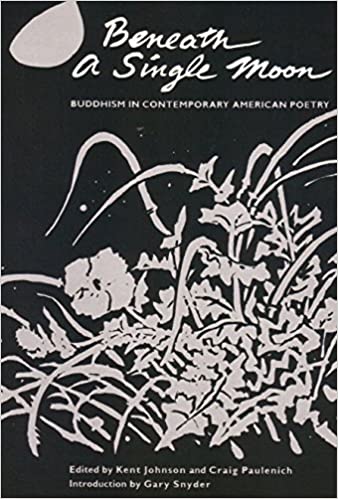

Beneath a Single Moon: Buddhism in Contemporary American Poetry

Edited by Kent Johnson and Craig Paulenich.

Shambhala Publications: Boston, 1991.

400 pp. $22.50 (paperback).

During the last four decades a stream of Buddhist awareness has been flowing in an underground and almost silent fashion through the arts in America.

Yet, almost paradoxically, although Buddhism has had its strongest influence on poetry, Beneath a Single Moon is the first anthology to bring together a broad range of Buddhist poets. It is also the only one to give poets room for essays on their practice and their art. In these two respects it is an important and seminal work. It succeeds not only in drawing us into the fabric of separate daily lives but provides as well a vision of being, as in Jane Hirshfield’s description of Indra’s net, where “all things are joined by a wide mesh in which every knot is a jewel, each jewel a universe, and all of them glimmer in the reflected light of one-an other’s existence.”

Every major Buddhist tradition is represented here, and Gary Snyder’s thoughtful introduction leads the reader into many of the elements common to the different forms of practice: “No one—guru or roshi or priest—can program for long what a person might feel or think. . . . we learn that we cannot in any literal sense control our minds…The mind essentially reveals itself.”

Beyond Snyder’s introduction, the book provides many subtle insights into lives lived in clarity of mind, as when Jim Harrison discusses sitting: “We should sit after the fashion of Dogen or Suzuki Roshi: as a river within its banks, the night sky in the heavens, the earth turning easily with her burden. We must practice like John Muir’s bears: ‘Bears are made of the same dust as we and breathe the same winds and drink the same waters, his life not long, not short, knows no beginning, no ending, to him life unstinted, unplanned, is above the accident of time, and his years, markless, boundless, equal eternity.'”

Likewise, in “Sitting Zen, Working Zen, Feminist Zen,” Sam Hamill writes about raking sand. “There is plenty of sand to be raked, and indeed some of it seems at first to be the sands of one’s own life, sands of the hour-glass, or sand from a remembered beach. ‘Samu’ suggests a rightmindfulness toward one’s work, toward all of one’s work. Raking the sand, one sifts through illusions and deceits, through guilt and embarrassment and anger, until, eventually, slowly and carefully raking the sand, one gets at last to the sand.”

Dianne Di Prima articulates the response of the first generation of American poets, herself as well as Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Whalen, to the prospect of the world as unconditioned: “A kind of clear seeing, combined with a very light touch, and a faith in what one came up with in the work: a sense, as Robert Duncan phrased it years later, that ‘consciousness itself is shapely.’ A kind of disattachment goes with the aesthetic: ‘you’—that is, your conscious controlling self—didn’t ‘make’ the work, you mayor may not understand it, and in a curious way you have nothing to lose: you don’t have to make it into your definition of ‘good art.’ A vast relief.”

In the hands of less accomplished poet/practitioners, this aesthetic has become almost a conditioned response. In Di Prima’s hands, it appears effortless and, at the same time, seems to release itself with the necessity of revelatory vision, as in these lines from “Trajectory.”

now no more blood runs

from the wounded Earth. our hope

lies in the giant squid that Melville

saw, that was

acres across. our hope

lies in the insect world, that the

rustling

Buddha of locusts, of ants, tarantulas

of scorpions & spiders

teaching crustacean compassion might

extend it

to our species.

(the Hopi say that it’s been done

before

and plant their last corn before coal

mines destroy the water table) a child of

mine waits to be born in this. Tristesse.

Tristesse.

John Cage and Jackson Mac Low present the poetry of chance, of nonintention, or as Cage puts it, “asking questions instead of making choices.” Mac Low shifts a little to the side and tells us, “Being ‘choicelessly aware’ is perceiving phenomena—as far as possible—without attachment and without bias. Art works may facilitate this kind of perception by presenting phenomena that are not chosen according to the tastes and predilections of the artists who make them.”

One of the strongest moments in the book is Anne Waldman presenting her own insight into dharma, and, by extension, the insight of American women at large. “I need to join the woman principle (prajna) in the man in me with the man principle (upaya) in me. . . . Gary Snyder commented that perhaps now, with the availability of the Vajrayana path, which seems to work the most provocatively of all the Buddhist traditions with female energy, women seeking liberation could realize their power fully and passionately. I instantly visualized Vajrayogini with her three eyes, skull bone necklace, and tiger skin ’round her waist, stomping on the corpse of ego.”

In her poetry, Waldman presents the eternal feminine energy of decoration. Within the freedom of “empty” space she finds room for enhancement, for the filled out and boundless as well as the “empty” nature of shunyata.

Look what thoughts will do Look

what words will do

from nothing to the face

from nothing to the root of the tongue

from nothing to speaking of empty

space

I bind the ash tree

I bind the yew

I bind the willow

I bind uranium

I bind the uneconomical unrenewable

energy of uranium

dash uranium to empty space

I bind the color red I seduce the color

red to empty space

I put the sunset in empty space

I take the blue of his eyes and make

an offering to empty space

renewable blue

I take the green of everything coming

to life, it grows &

climbs into empty space.

Many American Buddhists have had difficulty at some point or other with the traditional student-teacher relationship. Here our deeply ingrained individualism comes into conflict with Buddhism’s long oral and “mental seal” transmission of the Buddha’s teaching. “Do-it-yourself” America versus 2,500 years of highly evolved monastic disciplines. Armand Schwerner’s courageous essay deals, in part, with this relationship. “We’re often taught that the achievement of the state of true studenthood depends upon the capacity to transcend the unenlightened fear of pain, the capacity to experience the workings of faith, grace and seminal confusion. We think of Milarepa, who was able in his cave to dispel the demons of the mind, seeing that they were merely the demons of the mind. Thus we know that skeptical questioning may help to protect against some disease.”

Like the jeweled knots in Indra’s net, each piece both encompasses and reflects the whole, or, as Jane Hirshfield writes, “Each of our poems names and holds our connected life in this time, in this place, as each spring of water is the storehouse of a particular flavor of earth, each ear of corn the storehouse of weather, of soil. . . .”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.